SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STATUTE FOR AUTONOMOUS ADMINISTRATION

Author: Prof. Enes Durmišević, PhD, Faculty of Law of University of Sarajevo

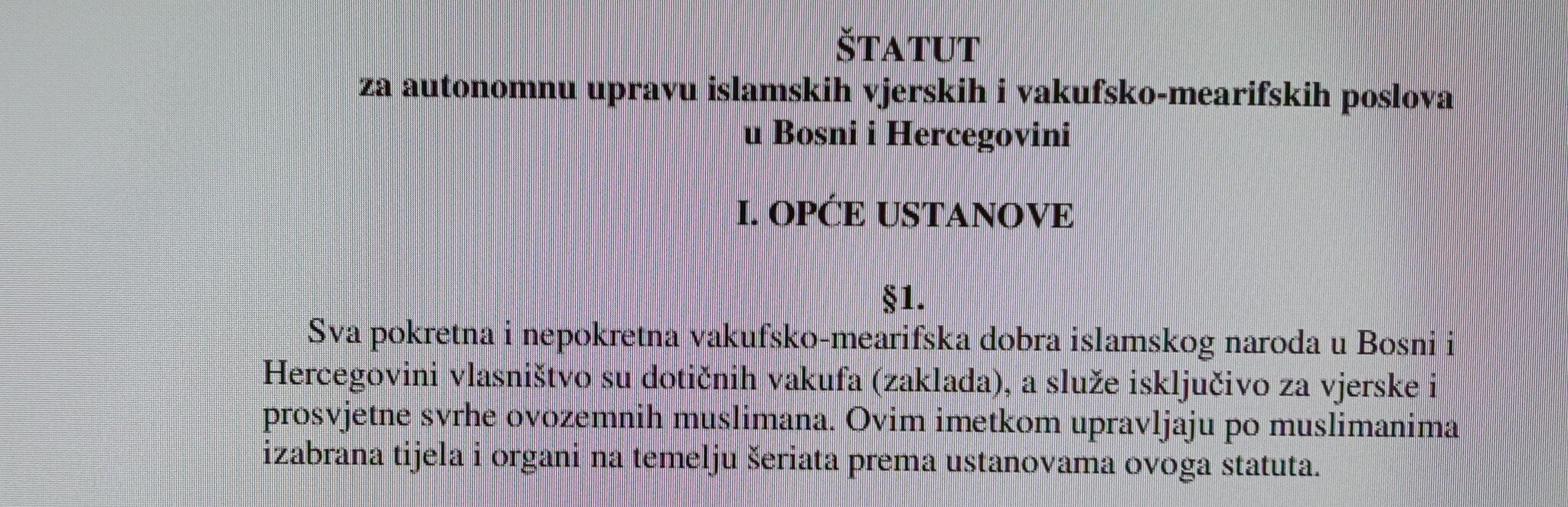

• Illustration: The Statute for Autonomous Administration of Islamic Religious, Waqf and Educational Affairs was issued on 15 April 1909.

Institutionalization of the independent Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina began after Austro-Hungarian occupation in 1878. Upon establishing the position of raisu-l-ulama and forming the Riyasat of the Islamic Community in 1882, Bosniak soon expressed opposing attitude toward occupation authorities.

Bosniak public at large were dissatisfied with usurpation and management of waqf property, Muslim schooling, position of raisu-l-ulama and Islamic Community, agrarian policy etc. It is for all these reasons that the year 1899 saw the beginning of Muslim movement for religious and waqf-education administration led by Mostar mufti Ali Fehmi-ef. Džabić. In a later stage, the movement would get political dimensions as well, and lead to the development of the first political party of Bosniaks – Muslim People's Organization, led by Ali-bey Firdus, in 1906.

Meetings of opposition politicians and opponents of the occupation administration gathered around mufti Ali Fehmi-ef. Džabić in Mostar reading room (kiraethana) assumed an increasingly political character. Original requests for preventing proselytism of the Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina were expanded daily, and resulted in often asked questions about the work of the Islamic Community management to those about general position of Bosniaks under occupation administration.

Management of the Islamic Community was accused of poor education of Bosniaks, poor management of waqf assets and religious schools (maktabs and madrasas), and school textbooks which insulted Islam which were published by occupation authorities without an energetic opposition by the top of Islamic Community. Consequently, autonomy was requested in managing religious, waqf and education affairs. In this respect, it was requested that occupation administration be deprived of any competences in these affairs, particularly in the election and control of work of waqf and education bodies.

Such requests gained ground in whole Bosnia and Herzegovina and found followers in Travnik, Sarajevo, Banja Luka and other cities. Very soon, a petition (memorandum) was submitted the minister of finance Benjamin Kallay, with the new draft of the Statute for Religious and Waqf-Educational Autonomy.

Austro-Hungarian authorities attempted to deny claims about abuse of waqf assets, providing statistical data on its improvement and claiming that waqf administration was organized pursuant to Islamic regulations and managed by the most renowned Bosniaks. They rejected all objections pertaining to waqfs, claiming that Bosniak landowners linked the issue of waqf management to their requests of purely agrarian nature with the aim of raising interests of their class to the level of general Islamic ones and thus prove that threat to beys' interests implied a threat to interests of the whole Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In this way, they wanted to raise their reputation among Bosniak public at large and assume the attribute of guardians of the Islamic Community.

This memorandum proposed a new scheme of organization of the Riyasat, i.e. Ulama-Majlis managed by raisu-l-ulama, and position of muftis. Ulama-majlis would consist of five members, who would be selected by the National Waqf Board, while the joint minister of finance would appoint raisu-l-ulama from among them, thereupon requesting the manshur from Mesihat in Istanbul.

With the aim of underscoring independence of religious, waqf and educational bodies from occupation authorities, draft of the Statute provided that persons who were public servants (army, administration offices etc.) could not be members of waqf, educational or other bodies.

It particularly highlighted that decisions of Mesihat in Istanbul were final in particularly important matters and in cases of interpreting ambiguous religious views.

The most sensitive issue in the negotiation between Land Government and representatives of Bosniak autonomous movement was election of raisu-l-ulama and granting the manshur, which was supposed to be issued by Shaikh al-Islam from Istanbul, because it opened the issue of relationship between Bosniaks and the caliph, i.e. Ottoman sultan, while Austro-Hungarian authorities wanted to severe these ties at any cost. All these issues which pertained to the Riyasat, i.e. constitution of highest bodies of religious and waqf management (election of raisu-l-ulama, members of Ulama-majlis and members of National Waqf and Educational Board) were resolved by the Statute for Autonomous Administration of Islamic Religious, Waqf and Educational Affairs, which was issued on 15 April 1909.

Pursuant to Article 131, out of three candidates nominated by the electoral body (Curia) composed of „30 persons of hodja class“, Austrian tsar and king selects one from among them and appoints him raisu-l-ulama. Thereafter, the electoral Curia sends a request, through Austrian official mission in Constantinople, to Shaikh al-Islam asking him to issue the manshur to the newly appointed raisu-l-ulama of Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In this way legitimacy of both the electoral spiritual Curia and raisu-l-ulama would be confirmed.

This electoral spiritual curia was granted exclusively the right to nominate candidates for Ulama-majlis. With this compromise, Austro-Hungarian authorities ultimately resolved the issue of their control of and supervision over the election and the manner of forming the highest bodies of Islamic Community and religious, educational and waqf administration, since a person who did not have the support and approval of occupation authorities could not be selected for raisu-l-ulama, a member of Ulama-majlis and a mufti.

In this way, the status and framework of activity of the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and particularly issuing the manshur to raisu-l-ulama were definitely solved. With the adoption of the Statute for Autonomous Administration of Islamic Religious, Waqf and Educational Affairs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosnikas managed to obtain more rights in managing the Islamic Community, as well as waqf and educational affairs under Austro-Hungarian occupation. However, the obtained self-management of religious, waqf and educational affairs had limited significance, since occupation authorities maintained their competences in the most significant issues in these areas. Although results of Bosniaks' autonomous struggle were significant, they were diminished by the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 7 October 1908, since it implied de iure abolishment of the sovereignty of Ottoman sultan over Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Immediately after issuance of the Statute, raisu-l-ulama of the time Azapagić resigned, and the new raisu-l-ulama hafiz Sulejman-ef. Šarac was selected and appointed pursuant to provisions of the Statute, i.e. he was issued the manshur by Shaikh al-Islam from Istanbul. The acquired autonomy of the Islamic Community was revoked in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1930, when raisu-l-ulama Čaušević refused to submit himself to the dictatorship of king Alexander and his control over the Islamic religious community.

The Statute for Autonomous Administration of Islamic Religious, Waqf and Educational Affairs was issued on 15 April 1909.

References:

Kapidžić, Hamdija (1956), Borba za vjersko-prosvjetnu austonomiju bosansko-hercegovačkih Muslimana 1899-1909., Enciklopedija Jugoslavije, vol 2, izdanje Leksikografskog zavoda FNRJ, Zagreb.

Karčić, Fikret (1990), Društveno-pravni aspekt islamskog reformizma, Islamski teološki fakultet, Sarajevo.

Kraljačić, Tomislav (1987), Kalajev režim u Bosni i Hercegovini (1882-1903), Veselin Masleša, Sarajevo.

Spisi islamskoga naroda Bosne i Hercegovine, u stvari vjerskoprosvjetnog uređenja i samouprave, Rad, Novi Sad, 1902.

Šehić, Nusret (1980), Autonomni pokret Muslimana za vrijeme austrougarske uprave u Bosni i Hercegovini, Svjetlost, Sarajevo.