APORIAS OF THE MUSLIM WOMAN ISSUE

Autor teksta: Meho Šljivo, MA, Riyasat of the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina • Ilustracija: WEB

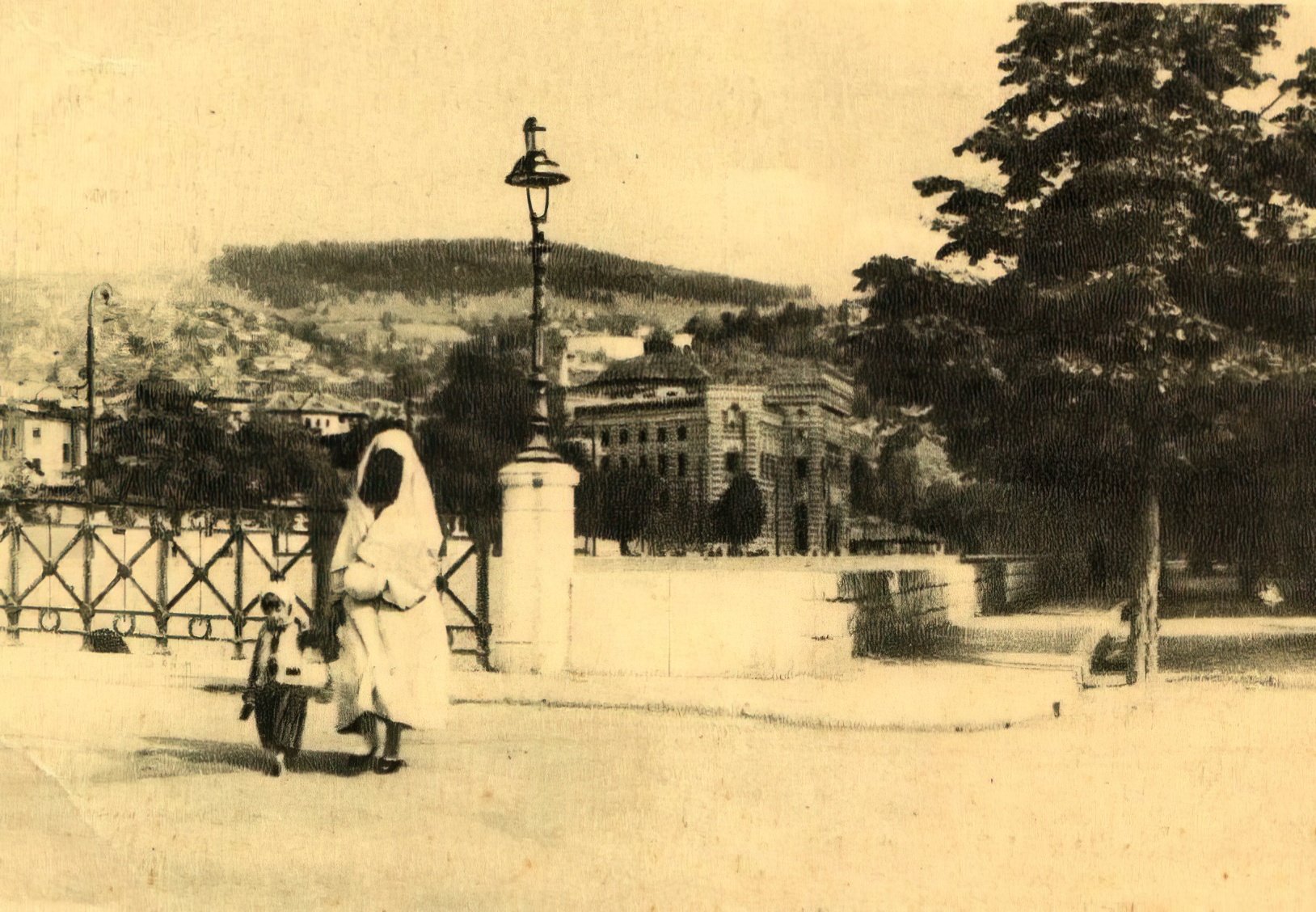

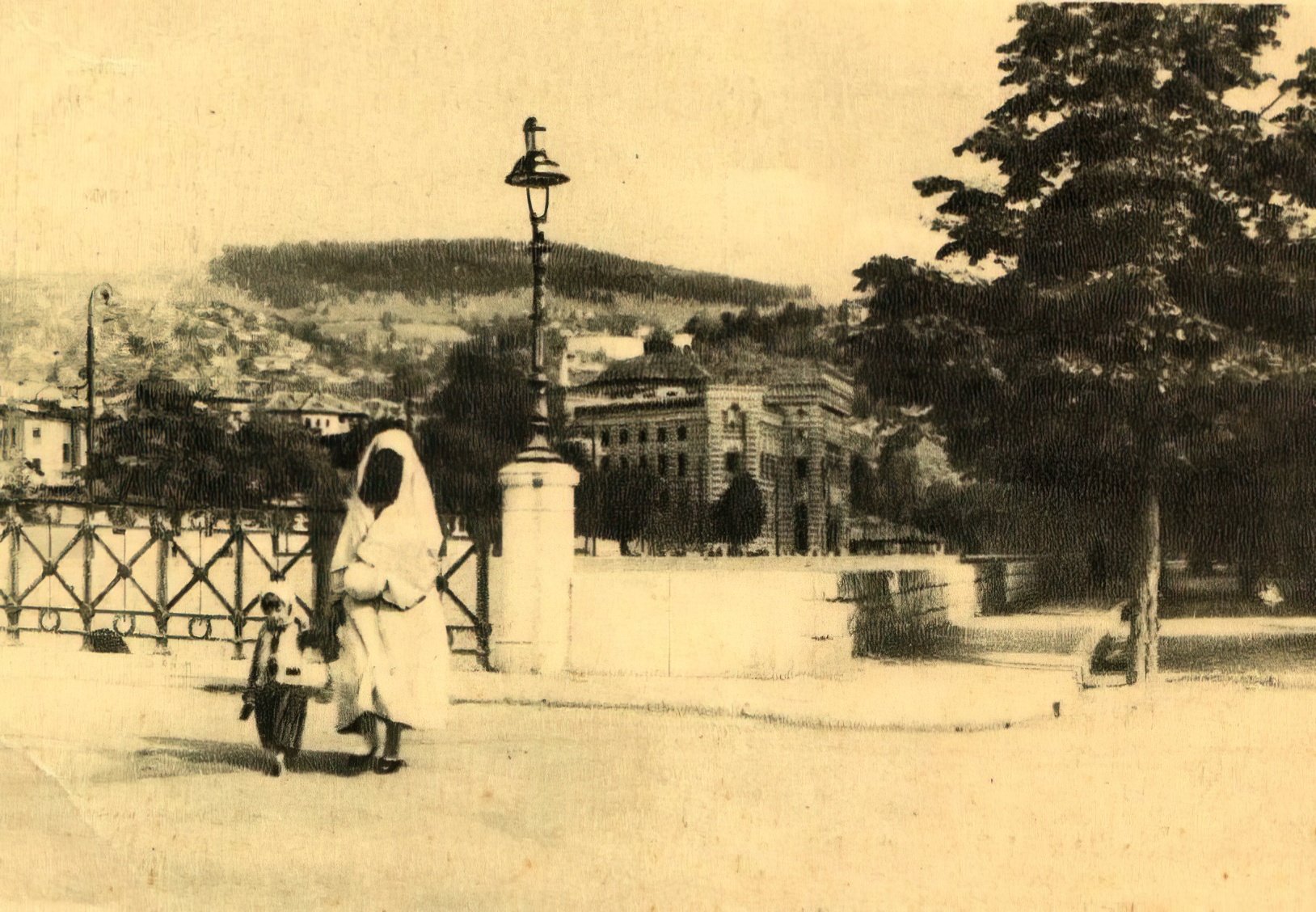

If you happen to walk from the cult café “Fis” in Sarajevo downtown toward the core of the city, you will probably go along Mis Irbina Street.

The street was named in the honor of a well-known Englishwoman of aristocratic origin, Miss Irby, who arrived in Bosnia in 1866. She had previously obtained the permit from the authorities of the Ottoman Empire to open a school in Sarajevo where only Christian girls could enroll. From brief available biographies about her professional engagement we learn, among other things, that Miss Irby “expressed a great interest in Slavic provinces, which were then still ruled by Ottomans”. The school which she opened in Sarajevo and managed very successfully eventually obtained a status of the Secondary Teacher’s School. Miss Irby stayed in Sarajevo for the rest of her life and was buried there, next to her long-time friend Staka Skenderova, a teacher from Sarajevo.

Several decades after Miss Irby's arrival in Sarajevo Bosnian Muslims looked for a Miss Irby of their own. Indeed, Arabic and Persian, languages that they could fluently speak, study and write in for over five centuries, were no longer officially used after the Austro-Hungarian occupation. The switch to the Latin and Cyrillic alphabet was a cultural-civilizational shock for them, and they could not deal with it without serious spiritual and social disturbances. Muslims felt that now “the carriage of history is rolling over them” on their own skin, and that their lives were irreversibly drowned in the huge majority of Christian peoples and under Christian administration and, as such, that it was inevitably oriented toward painful reforms in line with the spirit of a new age and the new European culture.

One of the most frequent questions of Muslim public of the time pertained to the right of the Muslim woman to education and to her powerful participation in public life. The obstacle for progressive exercising of the right was recognized, by part of ulama, reformers and intelligence of the time, in the deeply rooted custom of covering the woman's face, embodied in wearing the zar (veil) and the feredža (head-cape with a veil). For as long as three decades of the first half of the 20th century, various journals, brochures and other publications were full of an intense debate about whether and under what circumstances the Muslim woman was allowed to uncover the face in public.

Prominent entities of Bosniak people of the time, such as the Islamic Community, the most powerful Bosniak party – Yugoslav Muslim Organization and various Bosniak societies such as “Gajret”, “Narodna uzdanica”, “Muslimanska ženska zadruga”, “Spas”, “Hurijet” and others, actively and publicly confronted opposing and irreconcilable views of the so-called “Muslim woman issue”.

Moreover, the Muslim woman issue was gradually institutionalized. In an interview of 1927, to a journalist's question as to whether the emancipation of Muslim women in Turkey was in line with religious regulations of Islam, Džemaludin Čaušević provided the following answer:

Hiding women (...) is a deeply rooted custom, but religious provisions are not opposed to uncovering the face. Religion generally has nothing against it, but understanding of an individual and raising children which our women experienced, and which over centuries came through Turks, are opposed. There are tons of books which had been used at schools which say that the girl should cover the face and stay away from strangers as soon as she turns 12. However, here is what I am wondering about: our girls who enroll in universities and study to become doctors and other professions, can they study and attend lectures and science with their faces covered?!

Continuing to argument his views, rais Čaušević challenges the formalist and dogmatic approach to uncovering the woman's face with logical and moral counterarguments:

I would be more in favor of a Muslim woman who earns her living in an honest way, let's say in a store or a workshop, than of one with the covered face, who walks on the promenade and spend nights in pubs.

And while ultraconservative and traditionalist circles insisted that raisu-l-ulama withdraw and deny such a statement about uncovering the woman's face, the rais was wholeheartedly supported by prominent intellectuals, writers and public figures from the circles of secular and religious intelligentsia: Osman N. Hadžić, Abdurezak Hifzi Bjelevac, Hafiz Ajni Bušatlić, Dževad Sulejmanpašić, Šaćir Dedić Lutvica, Adem Bise and others. Muslim public did not lie low. Support for the rais was expressed by organizing meetings and conferences in Sarajevo, Belgrade, Zagreb, Mostar and Tešanj.

It would be wrong to think that the rais's statement about uncovering Muslim women's faces was impulsive, rash or said only under the impression of his short stay in Turkey. Eight years before this statement, in 1919, the first Muslim female doctor in Bosnia and Herzegovina – Ševala Zildžić Iblizović – requested and obtained approval of raisu-l-ulama Džemaludin Čaušević to enroll in all-boy high school. This event by itself testifies that the Muslim woman issue had been a subject of continued controversies and challenges in the public discourse, with active participation of Muslim women, for a long time already.

The electoral curia of hadjis – a high autonomous religious body which elected candidates for raisu-l-ulama and members of majlis – also responded to rais's views of uncovering the face, by issuing the so-called Takrir. By this takrir (public communication), the curia of hadjis identified the practice of covering the face with moral behavior. Briefly, their view of the issue was as follows: uncovering the woman's face and hands, as well as the man's watching them, is allowed if there is no fear that this activity will arouse passion. There is no Sharia obstacle to uncovering the face in case of the education of women, studies, trade and any honorable occupation.

The discussion of uncovering the woman's face was ended by Husein-ef. Đozo, when he published, in the journal Novi Behar in 1938, the view of the issue by the oldest and largest Muslim university El-Azhar. In a long reply to a question asked from India, which says that a group of Hindus is willing to embrace Islam but that they do not like covering women and circumcision (sunnet) and that it is why they are uncomfortable about converting to Islam, we find the following passage:

All the capacities of Islamic science agree that the woman's face and her palms can be uncovered and that they are not a defect, a shameful spot, and that she can work outside the home, be involved in a craft and earn her living, under the condition that she does not reveal body parts which may provoke men. The latter part is prescribed by Islam only to preserve the society and to prevent passion to undermine its foundations. Thus, Islam does not prescribe women to live like animals and be kept in prison like a criminal; it rather orders them to be present in mosques during daily prayers together with men and to attend public meetings of Muslims, where important issues are discussed. Islam allowed the woman to say her opinion at these meetings. It also allowed her to get education like all men and to manage her property at her discretion. (...)

It clearly follows that Islam does not prescribe the woman to cover her face and thus it cannot be an impediment to those who think about embracing it.

From the present time and historical distance, the Muslim woman issue which was so ardently discussed a century ago reveals its multifaceted phenomenological distinctiveness conditioned by historical course, as well as logical contradiction conditioned by intellectual development. While Muslims in monarchist Yugoslavia, in the theoretical and cultural sense, only broached the question of the woman's emancipation and her fundamental rights to participate in public life in a non-Muslim society, in the countries with Ottoman administration societies and institutes founded by non-Muslim women with the aim of providing literacy programs and economic empowerment of women had been active for years. It took Muslims decades of public dialogue, intellectual debated as well as dry discussions, various insignificant polemics, “twisting and circumventing God’s words” to find an institutional answer to questions that were not of religious character but rather a matter of custom. Reasons for such cultural lag and orientation of mentality should partly be sought in the fact which is underscored by Enes Karić when he reminds that, in the early 20th century, Muslim intellectuals in the Balkans (Bosniaks, Albanians, Torbeshes and Pomaks) discussed issues of what clothes should be worn and what to do about old cemeteries while at the same time intellectuals of Christian peoples in the Balkans mostly dealt with the issues of state, political parties, nation and national institutions. It is obvious that after the fall of the Ottoman state European powers did not offer Muslim peoples the possibility of the existence of a state but only of religion.

On the other hand, confrontations between modernists and traditionalists and open hostilities among Muslim ulama and intelligentsia manifested on the example of the so-called Muslim woman issue clarify another important and interesting phenomenon: borders and divisions are the deepest and the thickest within the same cultural-civilizational circle.

Dževad Karahasan summarized this insoluble aporia, many times confirmed by history and experience, in the form of a rhetorical question:

Isn't the gap between sceptics and those who think they know, searchers and dogmatics, in Islam or Christianity, still deeper than the gap between Islam and Christianity, the East and Europe. I am afraid that the border which separates the East from the West is shallower, that it is easier to bridge than the border which separates the people who believe that they know and have to right to judge from the people who are judged, between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, between sceptics and dogmatics.

References:

Jahić, Adnan (2010), Islamska zajednica u Bosni i Hercegovini za vrijeme monarhističke Jugoslavije (1918-1941), Zagreb.

Karahasan, Dževad (2002), O jeziku i strahu, Sarajevo.

Karić, Enes (2003), Bosanke muslimanske rasprave, Sarajevo.