SAFVET-BEY BAŠAGIĆ – ARCHIVES AND CULTURAL MEMORY

Author: Sejdalija Gušić, MA, archival advisor

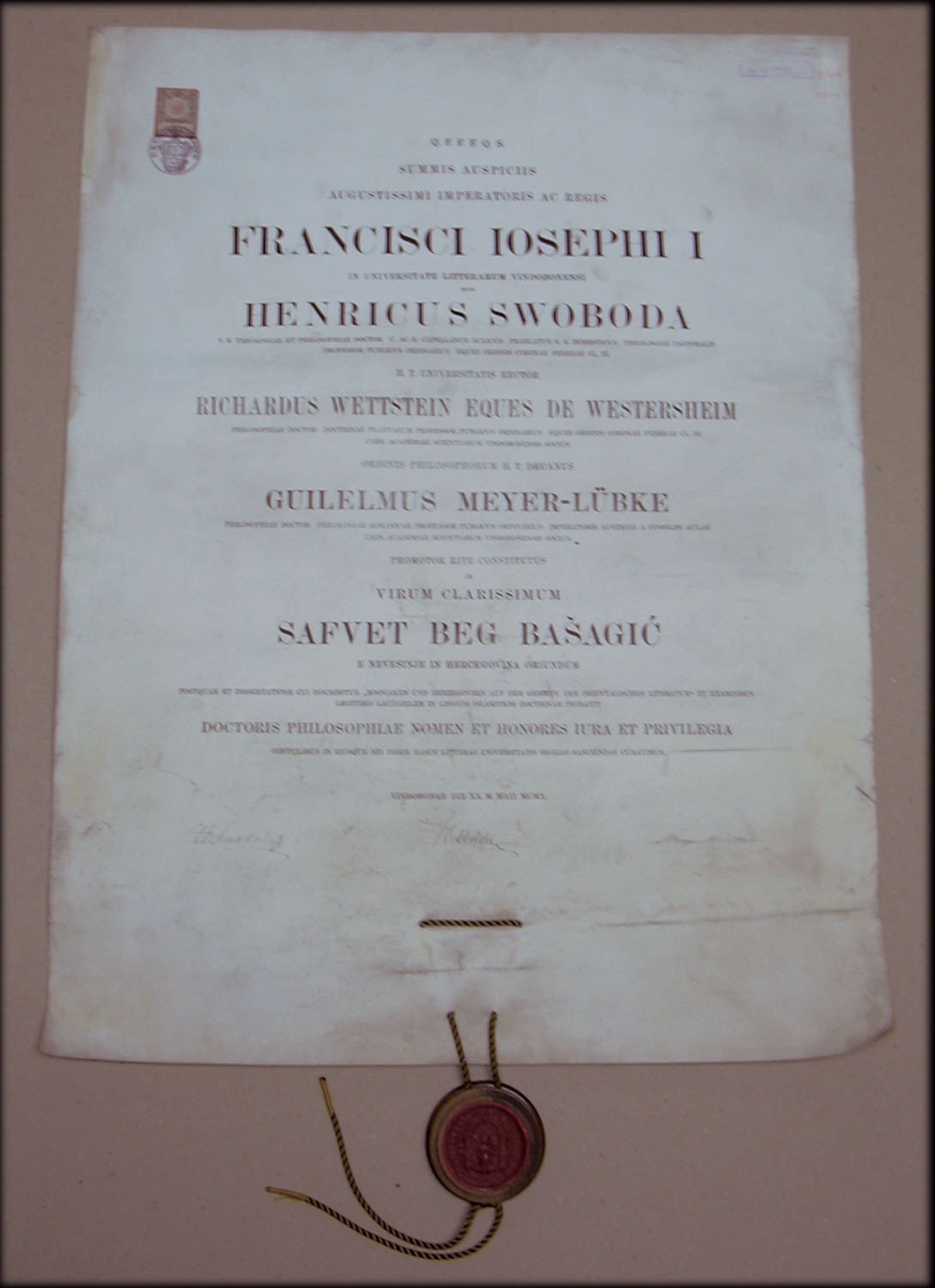

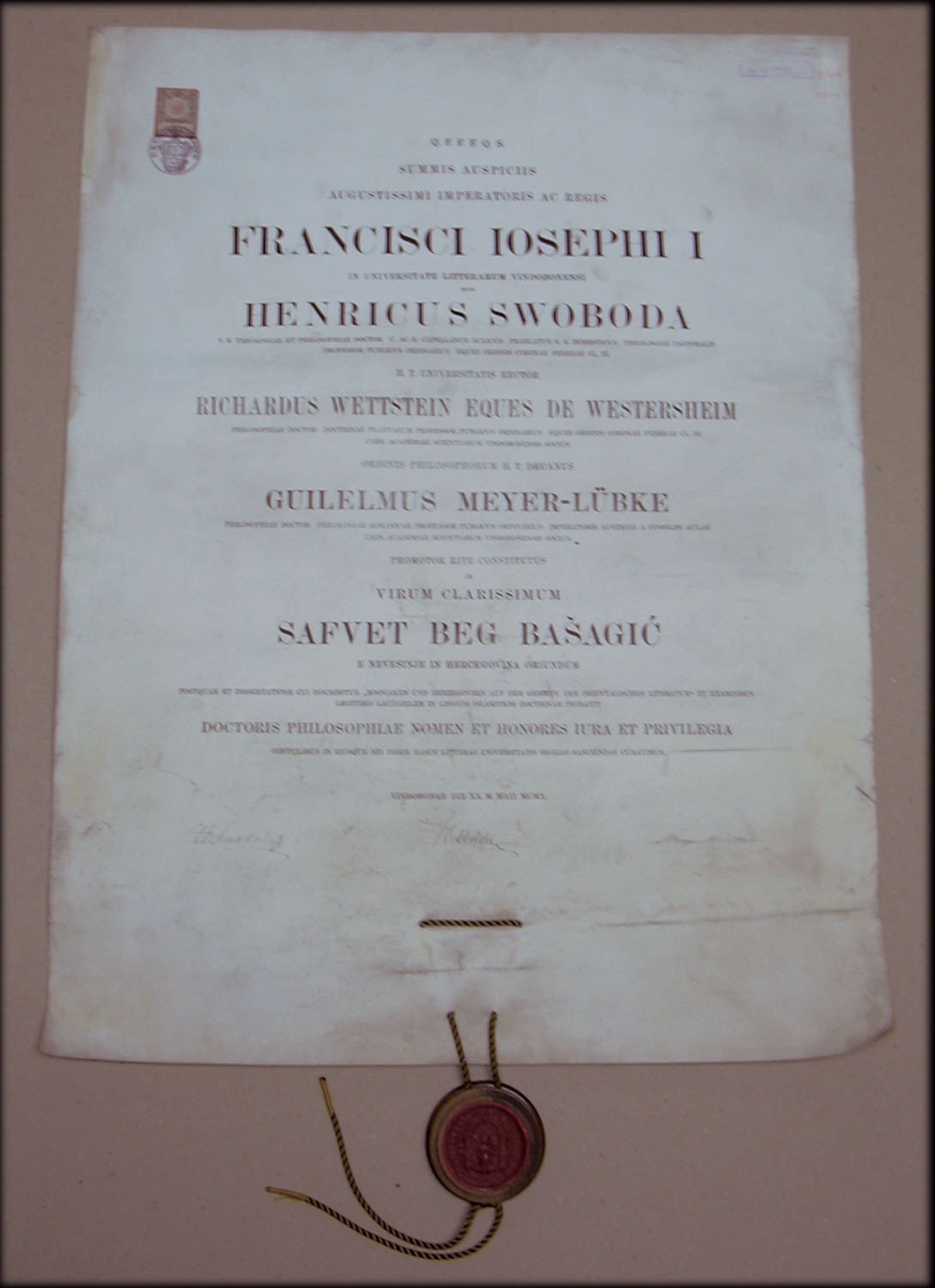

• Illustration: HAS, BS-17; 20 May 1910, Original certificate of doctorate with the seal of University of Vienna

If there is a person who can truly symbolize and authentically represent the social class of beys in Bosnia, both in its positive and negative sociopolitical dimension, it would without any doubt be Safvet-bey Bašagić. For him, belonging to the class of beys was not a mere title and a sentimental memory of the bright aristocratic origin of his famous Herzegovinian ancestors (from both paternal and maternal side); rather, it was Safvet-bey's destiny; his life philosophy; fundamental worldview; humanitarian and political orientation; the basis of his cultural, educational, artistic, scholarly and intellectual activity.

Bašagić Safvet-bey, son of Ibrahim-bey, a Bosniak writer, scholar, translator and politician, was born in Nevesinje on 6. 5. 1870, and died in Sarajevo on 9. 4. 1934. He received education in Sarajevo, where he became familiar with Oriental languages and literature. He was preparing to take a private graduation exam in Zagreb; however, due to his participation in laying the foundation stone for the Starčević Center (26. 6. 1894), Khuen-Héderváry's government prohibited it and he thus graduated in Sarajevo in 1895. Thereupon, he attended lectures in Oriental languages and history at the University of Vienna and taught Arabic in a Sarajevo high school for several years. He took his PhD in Vienna in 1920, having defended a dissertation about Bosniak writers in Oriental languages. In the same year he was elected a representative and then the chairman of the Bosnian Council, and therefore he could not accept candidacy for a professor of Oriental languages at the University of Zagreb. After the First World War until retirement, he was a curator in the National Museum in Sarajevo.

Safvet-bey was married to Fahrija Bašagić, daughter of Ćamil-bey Bašagić-Redžepašić and Najla Rizvanbegović. Safvet-bey and Fahrija had two sons: Fikret (and. 1916) and Namik (b. 1917, a bookstore owner), and two daughters: Almasa (b. 1913, married name Demirović) and Enisa (b. 1922, married name Knežić). Enisa graduated from the faculty of medicine in Zagreb.

As early as while he was studying in Vienna Safvet-bey Bašagiće began to collect material for the history of Bosnia. It was then that he wrote a study about the oldest ferman (decree) of Čengić beys. Thereupon he published Kratka uputa u prošlost Bosne i Hercegovine od 1463. do 1850 (A Short Instruction on the past of Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1463 to 1850) (1900), study Gazi Husrev-bey (1907), a literary-historical monograph Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u islamskoj književnosti (Bosniaks and Herzegovinians in Islamic Literature) (1912), and a biographical lexicon Znameniti Hrvati Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u turskoj carevini (Famous Bosniaks and Herzegovinians in the Turkish Empire) (1931). He was also involved in culture-related activities. Together with Edhem Mulabdić and Osman Nuri Hadžić he launched journal Behar in 1900, and in 1903 he founded societies Gajret, El-Kamer and Muslims' Club. In the cultural history of Bosnia and Bosniak literature, Bašagić is a key figure. Together with Musa Ćazim Ćatić, he was the first to attempt to synthesize the traditional sensibility (classical-Oriental on the one hand and folk-heritage on the other) with European literary heritage and procedures. In political terms, he was an advocate of the idea of integral Bosniak-hood.

“Post-occupation generation”

For years and decades, biography of Bašagić was written by various chroniclers, each in his own way and from his angle of looking at his turbulent and very interesting life (Hamdija Kreševljaković, Ivan Milićević, Hazim Šabanović, Alija Nametak, Muhsin Rizvić, Mahmud Traljić, Sajma Sarić, Muhidin Džanko and others); however, none of them engaged in writing an integral critical biography of Safvet-bey Bašagić which would not be a mere life story but rather a distinctive political, cultural, socio-psychological and intellectual portrait of this man, extremely interesting and significant for political, cultural and national history of Bosniak people.

Safvet-bey was lucky or unlucky (?!) to experience the arrival of Austro-Hungary in Bosnia at an early age and feel the “tide of new times”, which relentlessly brought about the European or, as people labelled it, “Kraut”, lifestyle: attending maktabs wearing shoes, using paper money, banking system, a new fashion (wearing the hat and the suit). However, essential changes in this revolutionary and critical time were far deeper, which was manifested in sudden impoverishment of beys and rebellions of non-Muslim population (Uprising of Nevesinje), in conservativism and disorientation of religious circles and perishing of supreme Islamic and state Turkish institutions; in fashion of the young generation who snobbishly accepted the European lifestyle (taking off the fez and the veil) though, at the same time, in fanatic rejection of new forms of life, particularly of schools and modern education.

Thus, Bašagić, with his intellectual personality and personal behavior, represented a paradigm of young Bosniak intelligentsia of the late 19th century, who faced barriers to accessing education in secular institutions which were rapidly established by the new Austro-Hungarian authorities. Maximillian Brown rightly labelled this scattered group of new Bosniak intelligentsia as the “post-occupation generation”. This generation voraciously absorbed new achievements of the European lifestyle and acquired modern knowledge.

Newspaper Novi behar wrote that until 9 April 1934 Sarajevo had not seen a more magnificent janazah that that of Safvet-bey Bašagić. The procession started from the Hrgića Street and the janazah was attended by 5,000 people. He was buried in the cemetery of the Bey Mosque in Sarajevo.

Archives and cultural memory

Upon Bašagić's death, the entire family documentation remained in the possession of his descendants, except for some documents written during his life. Many archival fragments left traces in various inventories and cannot actually be found. In 2003, his daughter Enisa Bašagić Knežić possessed, apart from some personal effects, lists of documents the existence of which cannot be verified.

Out of these materials, Ottoman documents were purchased by the Archives of Herzegovina in Mostar. As a matter of fact, Bašagić donated them to the cultural-historical collection of “Napredak” in 1933; however, in 1945, when this society ceased activity, Enisa took them over and gave it at the disposal of historians such as Hamdija Kreševljaković and Muhamed Hadžijahić.

In the 1960s, some descendants of Bašagić were fairly hard up and decided to sell these documents; therefore, Enisa offered them to the Archives of Herzegovina with the help of her husband, who in turn drew origin from Mostar. Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts formed an expert board, which was composed of archivist Ivan Esih (1898-1966) and orientalist Sulejman Bajraktarević (1896-1977). Bajraktarević processed the detailed inventory of the collection providing both brief and extensive contents of all the documents. The notebook was stored together with the collection and one copy was given to Enisa. Besides this copy, the rest of the inventory seems to have disappeared.

Archives of Herzegovina purchased the Ottoman collection for 3,500 dinars. During the 1992-1995 war it was edited by Šaban Zahirović, who had part of his work published in journal Hercegovina.

The Ottoman collection provides an insight into the life of Bašagić's ancestors and its most important part delas with the life of Safvet-bey's father, Ibrahim-bey Bašagić himself. It is for this reason that its publishing is interesting in the framework of the history of the 19th century in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In December 1966, Sarajevo Historical Archives accepted the offer of dr. Enisa Bašagić and Almasa Demirović Bašagić and purchased documents from the legacy of Safet-bey Bašagić for 12,000.00 dinars. They formed holdings entitled Bašagić dr Safvet-beg (call number. O-BS-279), which includes original manuscripts of Safvet-bey Bašagić in the area of literature, his translations, letters of many writers, cultural and public figures to Safvet-bey Bašagić, personal documents, some photographs etc. The archival material is incomplete; time span: 1885-1934; 5 boxes of records and notebooks; length<. 0.5 meters; well-preserved, thematically organized, accessible, languages: Bosnian, Arabic, Turkish, Persian, German; script: Latin, Arebica; analytical inventory completed.

At this point I would like to underscore the importance of Bašagić'e correspondence, which is stored at various archives. Unfortunately, it is not possible to trace the correspondence in both directions; in other words, except for few exceptions, we do not have letters which Bašagić sent to his friends and various people from the political and education sphere of his time. Instead, he, and later various institutions which inherited them, have only the letters which he received. Most of these letters are part of holdings of the Sarajevo Historical Archives. Besides, several letters can also be found in the Milivoj Dežman holdings of the Department of Literature of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (HAZU OK MD). There are also several autographs found so far or stored in various holdings, particularly in the Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ABH). Finally, some letters from Bašagić's documents entrusted to the society “Napredak” (cultural-historical collection of “Napredak”) have disappeared, although they are referred to in various articles written by his friends and admirers between the two wars. Thus, Munib Šahinović Ekremov made use of one notebook, where Bašagić copied three letters to his friend Bakir-bey Tuzlić, a well-known member of the Executive Board of the Movement for Autonomy, which he sent in 1910.

Out of the available inventories, I will list only a small number of people that Bašagić corresponded with: Alaupović Tugomir, Arnautović Mehmed, Barun Benko, Ana Bezdekova, Husein-beg Biščević, Mujaga Čišić, Milivoje Dežman, Osman Dujmović, Ida First, Smail-beg Ferizbegović, Kosta Herman, Ibrahim Kajtaz, Andrija Luburić, Gavro Manojlović, Vladimir Mažuranić, Edhem Mulabdić, Osman Aziz, A. Olesnicki, Ivo Pilar, Vladislav Skarić, Marija Strozzi-Ružička, Franc Babiger, M. Mrazović, Varešanin, etc.

Places of memories and remembrance, such as archives, museums, libraries, memorials and similar ones, are an expression of processes where people are no longer immersed in their past but rather read and analyze it. Now, the past is here to be archived, and therefore the places of memories and remembrance are a result of this almost archival and panic attempt to manage to save something from the past. While history is a kind of reconstruction of the past, memories are subject to continuous evolution, sensitive to appropriations and manipulations, subject to long latency and sudden revivals. It is for this reason that “cultural memory” is changeable and dependent on interpretations of the past which, as we here know only too well, change at times and very fast. Bašagić's collection of Islamic manuscripts and old books, which is owned by the University Library in Bratislava, was entered on the List of World Heritage in 1997, as part of UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Part of the collection is available online, through the World Digital Library.

Having in mind the fact that we keep talking about memory, since we no longer have it, it is necessary to be reminded of the view of Bašagić, to remember it: One nation can experience a political, social and economic fiasco in their homeland. All of it is temporary, everything can last for a day only. Still, they have something which is not transient, which cannot be a mere accident, which cannot be destroyed even by the fiercest enemy, and it is brainchildren which we call literature. This triumph remains forever, since it is a pledge to future generations and times.

Original certificate of doctorate with the seal of University of Vienna

REFERENCES

Sarajevo Historical Archives, Safvet-bey Bašagić holdings; (HAS; BS 279), analytical inventory.

Sajma Sarić, „Život i rad Safvet-bega Bašagića u dokumentima Državnog arhiva Bosne i Hercegovine“, Zbornik radova sa naučnog skupa ”Safvet-beg Bašagić - bošnjačka intelektualna strategija”, Zenica, 1994.

Muhidin Džanko, BIOGRAFIJA SAFVET-BEGA BAŠAGIĆA-REDŽEPAŠIĆA: Nepodnošljiva neizbježnost pozitivizma; Divan, 3-4, 2000.

Bašagić, Safvet-beg, Hrvatska enciklopedija, Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 2020.

Alija Nametak, Sarajevski nekrologij, 1995.

Autobiographical poem by Safvet-bey Bašagić entitled Kratak pregled mog života (A Short Overview of My Life); ”Gajret”, X/1926, 5, 66, 67.

Mateo Žanić, Od mjesta sjećanja do zajednica sjećanja – društveno označavanje prošlosti, Proceedings: Vukovar '91. – dvadeset i prva godina poslije – Istina i/ili osporavanje (između znanosti i manipulacije), 2013.

Safvet-beg Bašagić, Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u islamskoj književnosti: Prilog kulturnoj historiji Bosne i Hercegovine, Izabrana djela, vol. 3, ed. Džemal Ćehajić and Amir Ljubović, Kulturno nasljeđe Bosne i Hercegovine, Svjetlost, Sarajevo, 1986.