STARS IN THE EASTERN AND WESTERN SKY

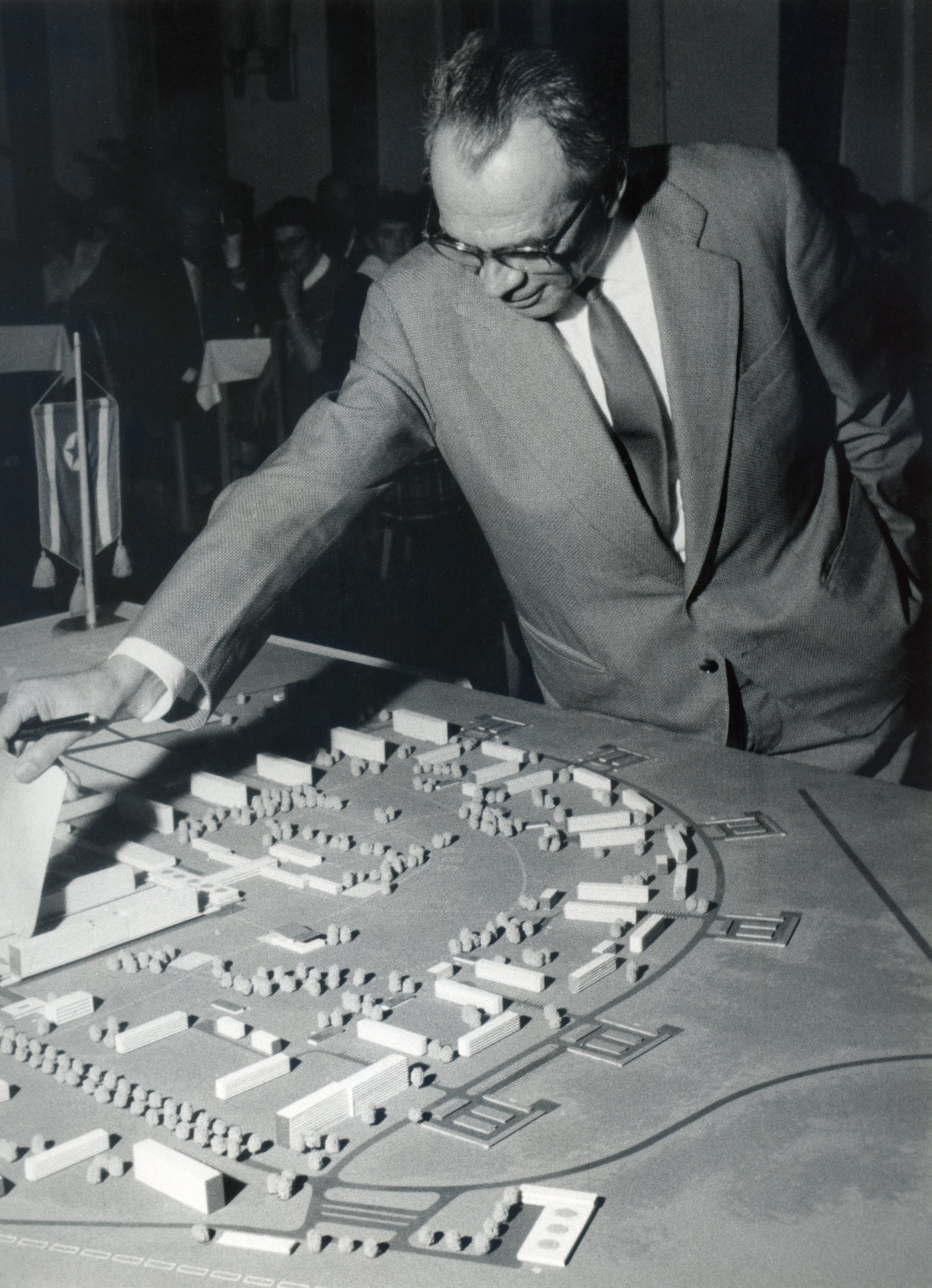

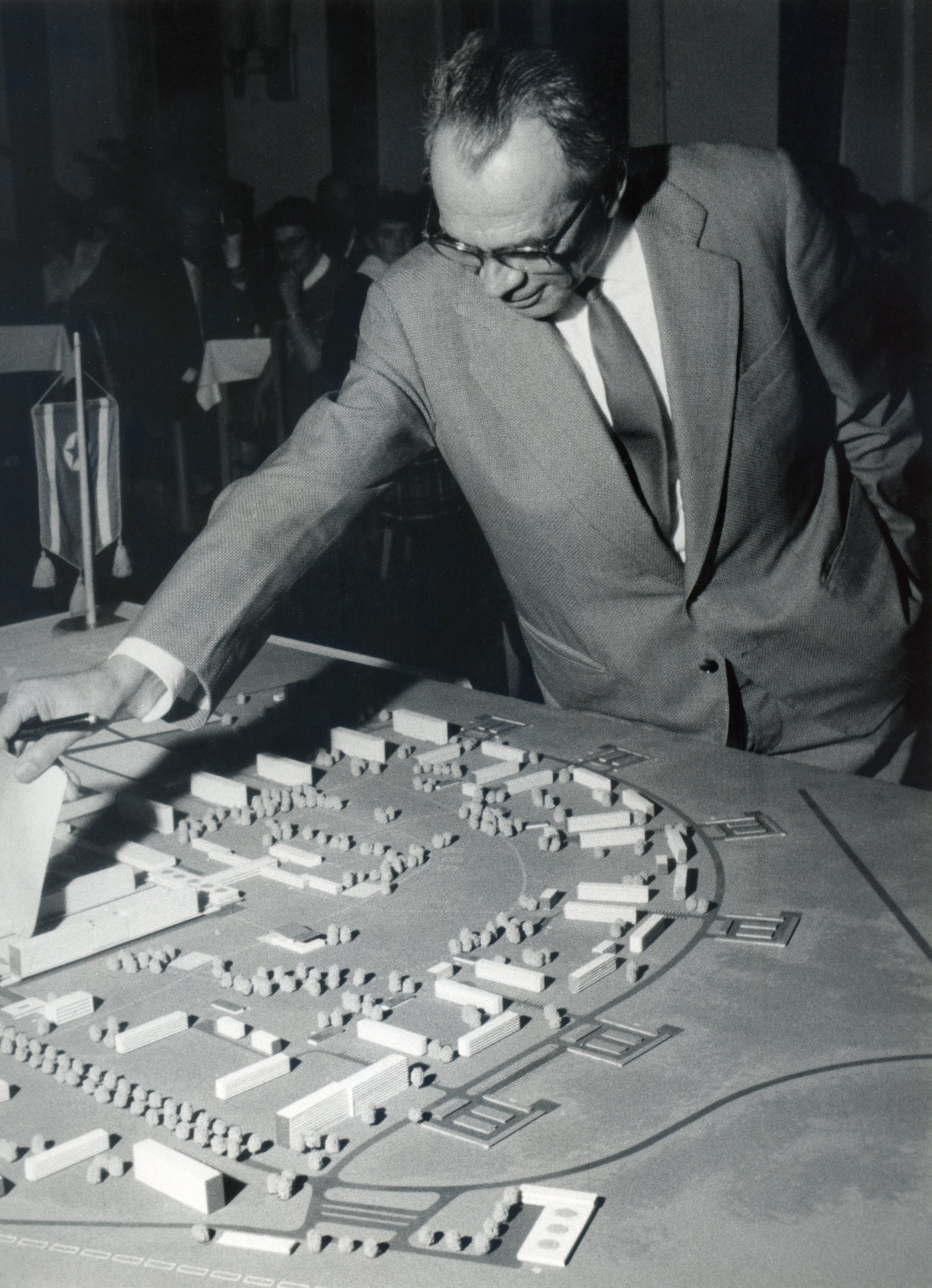

Author: Ekrem Tucaković, PhD, Riyasat of the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina • Illustration: Selman Selmanagić in front of the model of Schwedt town, late 1960’s • Photo: Selmanagić family archive, Berlin

“If one wanted to provide a short definition of the history of Bosniaks, he could say that it has practically been an incessant struggle for self-preservation on their own soil, in a hostile surrounding and that during this struggle, despite all the wars and suffering, Bosnian Muslim folk genius has created enviable works, in the field of both tangible and spiritual culture. Ever since the Vienna War (1683-1699) a constant struggle for survival and preservation of their own spiritual identity has been going on regardless of the inner class structure and intellectual diversification of the Bosnian Muslim society” (Imamović, 572).

Expansion of the Ottoman Empire to the medieval Bosnian Kingdom led to an immediate encounter of the inhabitants of Bosnia with a new religion (Islam), a new script (Arabic) and new languages (Arabic, Turkish and Persian). Many Bosniaks used the newly arisen opportunities to express their talents in many fields within the new civilizational framework. A significant number of Bosniaks held highest and high state and military positions (grand viziers, viziers, governors, beylerbeys, pashas, the highest judiciary and religious positions (kadiaskers /chief judges/, shaykh al-Islams /chief muftis/, muftis, cadis), and an extremely significant number grew into famous intellectuals and polyglots who authored literary works in Arabic, Turkish, Persian and Bosnian, wrote academic works, translated and commented on major works in various academic disciplines.

It seems that there are few so small geographic areas and small European nations which have shown so broad ability for creative integration and production as Bosniaks. Besides the recognition and contributions in the military and administration, the end of the 16th century “was in the sign of intellectual recognition of Bosniaks who were on the very top of the intellectual elite of the Ottoman Empire” (Husić, 179), and they thus powerfully promoted the Bosnian landscape within the largest and the most powerful world country of the time.

Safvet-beg Bašagić wrote biographies of over 680 Bosniaks who were prominent in public life in the Ottoman period, Mehmed Handžić presented over 200 scholars and poets, Hazim Šabanović also listed several hundreds of Bosniak writers and authors in Oriental languages, and Leksikon bošnjačke uleme (Lexicon of Bosniak ulama) presents biographies of 1859 Bosniak alims from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sandžak, Serbia, Montenegro and Croatia.

The second half of the 16th and early 17th century were the time of Bosniaks' strongest influence in the Ottoman Empire, where there were nine Bosniak grand viziers, a large number of viziers of lower ranks, and governors in provinces. The most influential personality of this age was Mehmed-paša Sokolović, a grand vizier during the rule of three sultans (Sulayman II, Selim II, Murad III). He was considered the informal ruler of the Ottoman State after Sultan Sulayman's death. Joseph von Hammer, the author of Historija Osmanskog carstva (The History of the Ottoman Empire) claims that it is more proper to say “during vizier Sokolović's rule” than “during the rule of Selim II”. Mehmed-paša Sokolović is the forefather of the most powerful family in the Empire in the second half of the 16th and the early 17th century, after the ruling family which provided four viziers. Besides, significant viziers also include the following Bosniaks: Ahmed-pasha Hercegović, Ali-pasha Hadum and Damad Rustem-pasha Opuković. Many Bosniaks left a significant trace across the Ottoman Empire as governors, cadis and scholars. Bosnian governor Gazi Husrev-beg is the most meritorious for the economic and spiritual development of Sarajevo in the 16th century.

Bosniaks wrote in Oriental languages as the fundamental languages of science and culture in the Eastern hemisphere, in all the fields which could be dealt with at the time (poetry and fiction, theology, medicine, mathematics, logic, alchemy, astronomy, philology, travelogues, historiography and others). By erudition and the power of ideas and views one can single out Hasan Kafi Pruščak and Mustafa Ejubović – Sheikh Jujo, who wrote many original works in the field of Islamic studies, Ali-dede Bošnjak and Abdulah Bošnjak, remarkable philosophers and gnostics, Derviš-pasha Bajezidagić, Fevzija Mostarac, Hatem Bjelopoljak, Sabit Užičanin, Muhamed Nerkesi and Zekerija Sukeri as prominent writers/poets in Turkish, Arabic and Persian. Muhamed Hevaji Uskufi was the author of the first Turkish-Bosnian dictionary and dictionary in general in South Slavic regions. Ahmed Sudi Bošnjak is still one of the most significant classical commentators of fundamental works of Persian literature. Nasuh Matrakči - called Ottoman da Vinci due to his academic and artistic achievements – was a personality of exceptional erudition and broad research and scientific range: physicist, mathematician, geographer, inventor, painter, navigator, sultan's counselor and swordsman.

According to recently presented data, two Bosniaks were elected shaykh al-Islams (the main religious leaders of the whole Empire, with the right of veto on issues related to education and justice). The first was Mustafa-ef. Bali-zade (Balić) from Foča, the 67th shaykh al-Islam, and the second was Mehmed Refik Hadžiabdić from Rogatica, 109th shaykh al-Islam (Popara, 26-27).

Departure of the Ottoman and arrival of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Bosnia in 1878 was far more than a routine relief of two empires, or a change in the ruling regime and system. It was a profound change in civilizational and spiritual paradigm, which was seen as a radical and violent breakup with everything that was Bosniaks' mental and spiritual privacy, that was familiar to them, dear and “sacred”, and an entry into a cultural-civilizational circle which was hostile according to their notions and experience, and one that they had waged wars with for centuries. It was followed by spiritual paralysis, a period which Muhidin Rizvić calls a “deaf age” in the field of literary creations. (Rizvić, 24). Enes Karić labeled this period in Islamic thinking as a “discourse of silence” or a “discourse with silence”.

The first years of shock and paralysis were followed by the creative power of integration into a new spiritual and cultural milieu, when Bosniaks, preserving their identity as Fikret Karčić, PhD says, opted for selective acceptance of the European cultural values after initially rejecting them. In line with this, in the early 20th century, an enthusiastic spirit of Bosniak revival was manifested, of a powerful enlightenment idea around the journals Bošnjak and Behar, which were promoted by Mehmed-beg Kapetanović Ljubušak, Safvet-beg Bašagić, Osman Nuri Hadžić, Edhem Mulabdić, Musa Ćazim Ćatić and many others. Ahmed Muradbegović, Hasan Kikić, Mehmedalija Mak Dizdar, Meša Selimović, Skender Kulenović, Derviš Sušić and Dževad Karahasan portrayed the world of Bosnia from the early Middle Ages until today by means of language and through the medium of literature, and have become recognizable literary names in regional and European literary circles. Safet Zec, Dževad Hozo, Mersad Berber and Behaudin Selmanović have gained world reputation by painting and drawing the world and the spirit of Bosnia, with techniques and forms of fine arts. Architect Selman Selmanagić, a successor of the German school Bauhaus, who worked in the team for reconstruction and development of Berlin from 1945 to 1950, is credited for the restoration of key facilities of Berlin cultural heritage such as Berlin Cathedral, Neue Wache, Humbold University and others. Another architect – Zlatko Ugljen – was the winner of Aga Khan's Award for architecture in 1983 for his project of Šerefudin's White Mosque in Visoko. Smail Balić's scholarly work was recognized in Austria and he was therefore awarded a state decoration – Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art, first class.

In entirely different epochs, divergent cultural-civilizational frameworks or opposite state systems, Bosniaks managed to manifest the power of Bosnian spirit, to show a great ability of the “transitive mind”, thus giving significant contributions to the society and human progress.

References:

Bašagić, Safvet-beg (1912), Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u islamskoj književnosti I, Sarajevo.

Bašagić, Safvet-beg (1931), Znameniti Hrvati: Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u Turskoj carevini, Zagreb: Matica hrvatska.

Husić, Aladin (2018), “Historijski kontekst pojave Ahmeda Sudija Bošnjaka”, Anali GHB, 47 (39), UDK: 28:929.

Imamović, Mustafa (1997), Historija Bošnjaka, Sarajevo: Sarajevo.

Karić, Enes (2011), “Vidovi islamskog diskursa u BiH od druge polovine XIX stoljeća do danas – historijski pregled”, u: Islamski diskurs u Bosni i Hercegovini: zbornik radova Naučnog skupa Islamski diskurs u/za BiH: stanje perspektive, prioriteti, Sarajevo: Institut za proučavanje tradicije Bošnjaka, Fakultet islamskih nauka, Centar za napredne studije.

Ljubović, Amir, Grozdanić, Sulejman (1995), Prozna književnost Bosne i Hercegovine na orijentalnim jezicima, Sarajevo: OIS.

Mehmedović, Ahmed (2018), Leksikon bošnjačke uleme, Sarajevo: Gazi Husrev-begova biblioteka.

Popara, Haso (2006), “Bošnjaci su imali dva šejhu-l-islama!”, Preporod, XXXVI, 6/824, str. 26-27.

Rizvić, Muhsin (1990), Bosansko-muslimanska književnost u doba preporoda (1887-1918), Sarajevo: Mešihat Islamske zajednice BiH, El-Kalem.

Šabanović, Hazim (1973), Književnost muslimana BiH na orijentalnim jezicima, Sarajevo: Svjetlost.