DERVIŠ OF ĐURĐEVIĆ: TIMELESS WEALTH OF DIVERSITY

Author:Vesna Miović, PhD, Institute for Historical Studies of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik

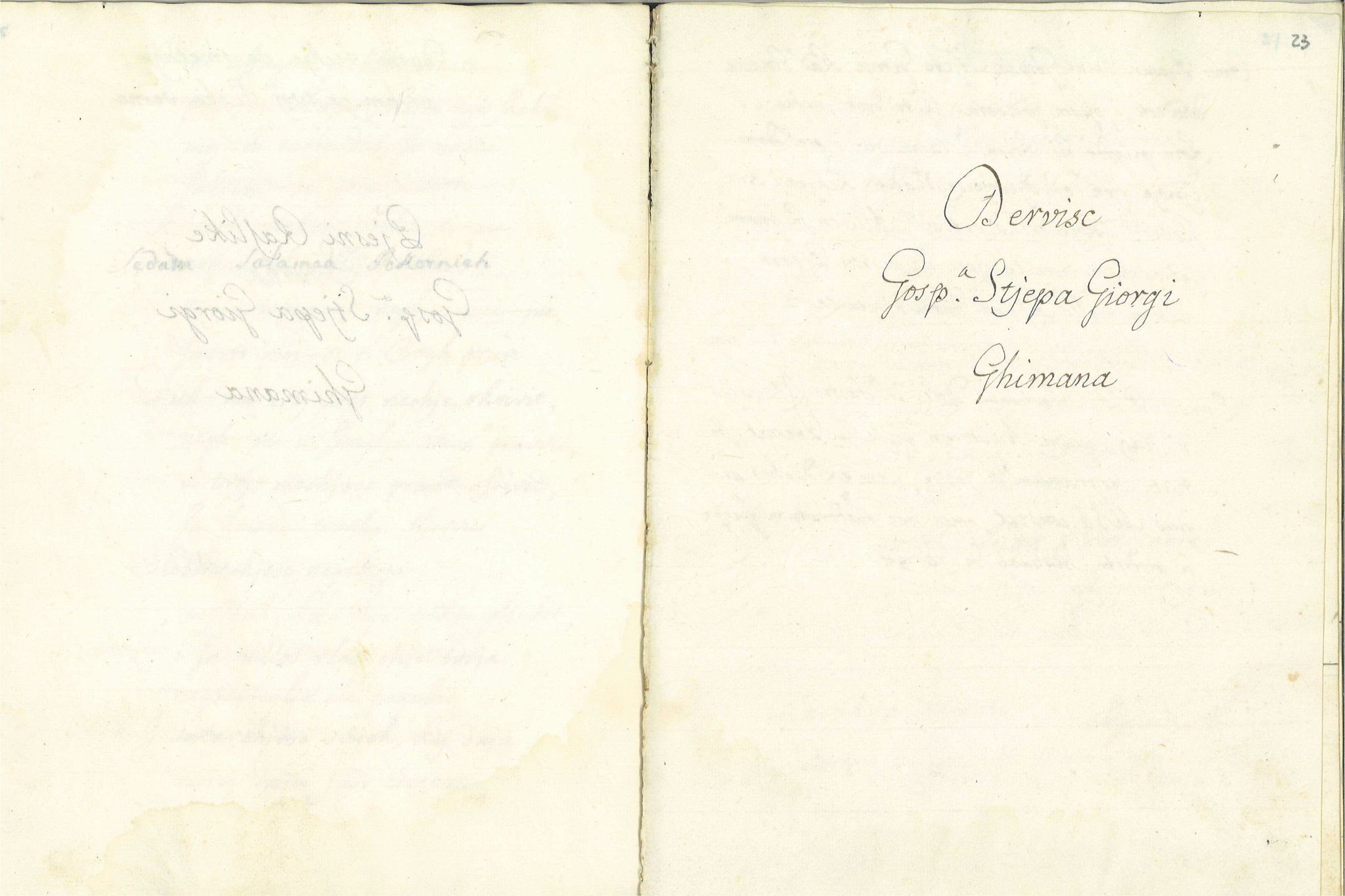

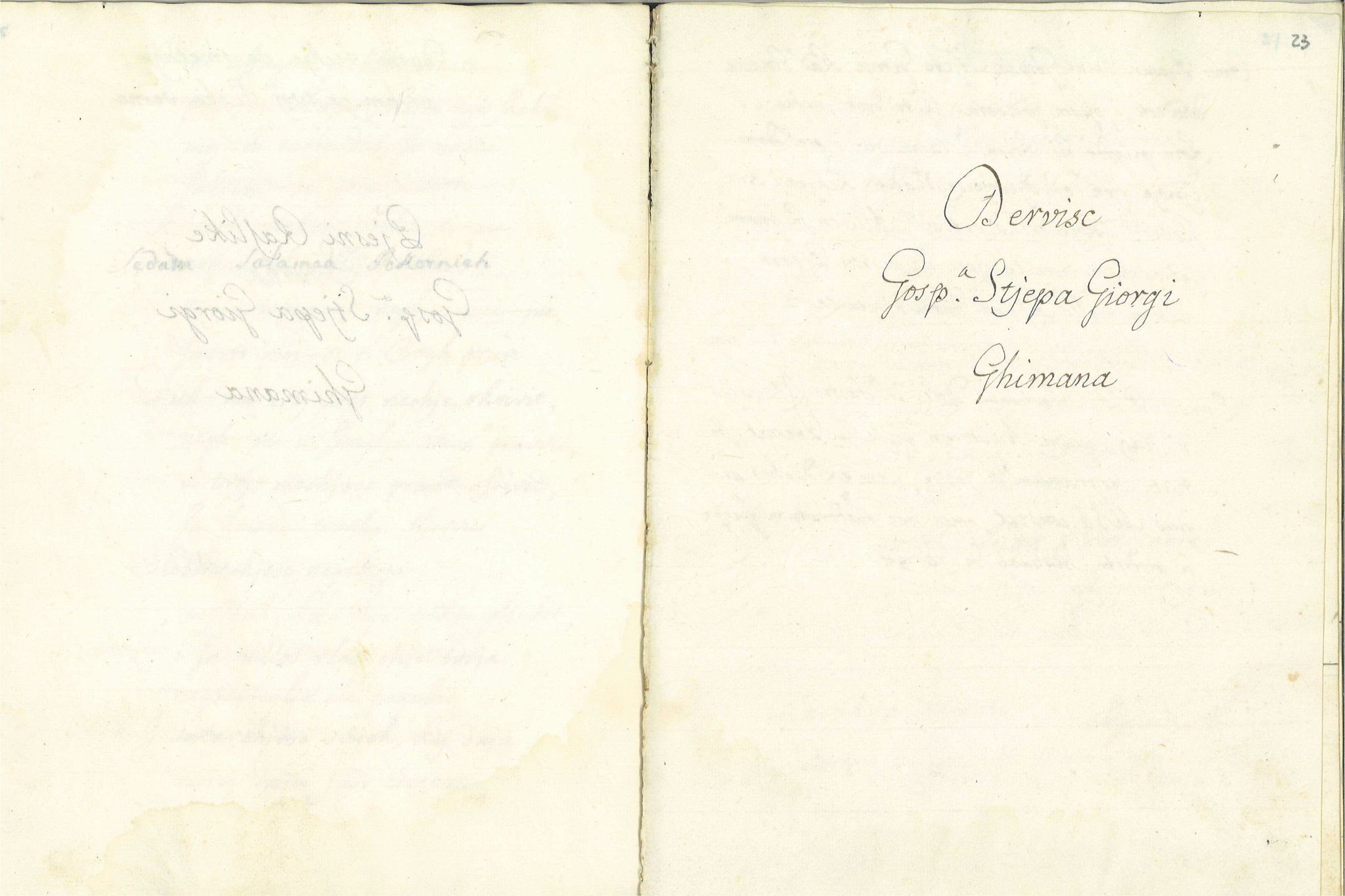

Illustration: The first page of the transcript of poem “Derviš” by Stijepo Giorgi (Đurđević) Giman, 18th century, Library of the Institute for Historical Studies of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik, collection Bizzaro.

All noblemen from Dubrovnik were mischievous and unbridled in their youth, but Stijepo Đurđević Giman (1579-1732) really stopped at nothing. Under cover of darkness he settled accounts in city streets with fists, a stick and a bludgeon, and easily unsheathed the sword. Once it was even suspected that he had committed a murder. For all these reasons he was in jail several times and paid high fines.

The Đurđevićs belonged to the circle of the patrician conspirator families from Dubrovnik who were involved in counter-Ottoman activities in the so-called Big Conspiracy. Since he helped his brother Jakov, an active conspirator, to flee from the Republic, in 1612 Stijepo was sentenced to four years' exile. It was for this reason that he never held significant state positions. He was a candidate for the rector of Dubrovnik only once, but people did not want to elect him.

Still, he remained remembered as a prominent nobleman of Dubrovnik, because he successfully committed himself to writing poetry. His best-known work is poem Derviš (Dervish), also known as Dervišijata in Dubrovnik of the time. The poem consists of 50 sestines interwoven with about eighty Turkish loanwords. Thus, it clearly shows that citizens of Dubrovnik had a sound knowledge of Turkish loanwords which were used in Bosnia, which is actually quite understandable.

The main character of the poem is a man who is hopelessly in love with a cold, noble girl. But why is the man a dervish? The legend goes that on one occasion, Đurđević was being taken to jail for some mischief when he heard the rector's daughter wondering aloud: “Who is this dervish?”. His heart trembled as soon as he looked at her and that is why he wrote a poem for her. He was twenty-eight at the time. Later on, the legend goes, the rector's daughter became his fiancée.

Since jails were situated in the Rector's Palace, the rector's daughter may have seen Đurđević's arrest. She probably compared him to a dervish because it was clear that asceticism was waiting for him in the cell. Of course, men and women from Dubrovnik knew who dervishes were. They would see them in Bosnia, and they also encountered travelling dervishes in Dubrovnik. Envoys from Dubrovnik, noblemen who took harač (tribute) to the sultan, regularly attended the Mevlevi dhikr. Marin Caboga, an envoy from 1706, described it as follows:

“They stood in a circle in their amphitheater, the holy people. While the dervish-hoja spoke to them from the pulpit and after he had said a short prayer, music began from a small choir and the dervishes stood up at once, having thrown back their upper dress, appeared in a kind of long skirt and a zubunić (upper dress, sleeveless or with short sleeves), clothes very similar to what our women from Pelješac (peninsula) wear. The dervish-hodja extended the arms and began to whirl, and the other dervishes followed, all around one after the other, but always whirling with an unspeakable speed. And this whirling lasted for about three quarters of an hour, with a break after each quarter.”

Only several transcripts of Derviš have been preserved to this day, and in each copy the transcriber explained Turkish loanwords. One copy is held in the library of the Institute for Historical Sciences of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik and the transcriber Ivan Altesti (1727-1816) decided to explain both Turkish loanwords and customs of dervishes. By doing so, he showed that he himself was fairly familiar with them. He described the tekke as a monastery of believers - dervishes who whirl, and also noted that dervishes typically wore a belt around the waist, that they carried a gourd for water and a cane, and that they wounded themselves with a razor.

The Dervish of Đurđević keeps speaking to his beloved to make her return the feelings. However, she keeps silent and at times looks at him unkindly and haughtily. For all these reasons his emotions and responses keep changing, from outburst of tenderness and love, utterances of hope and optimism, to deep depression, unbearable anguish and totally insane actions.

His love is Christian, but should it be a problem: “And if đuzel (beautiful) Mare of Cernica loved me as well, why don't you love me, I am old spruce Dervish”.

Beauty of a high-born girl is admirable: “O my spruce sultana (princess)..., you are a beautiful melek (angel) from paradise, ..., you are more beautiful than a shooting star, the sun, the dawn..., but Dervish is also notable: “I am not a čoban (shepherd), nor a bastard, no, I am not a kiridžija (paid wagoner), I am a kaduna’s (lady's) son, and my father is a čelebija (gentleman)”.

The cruel girl took his heart and soul: “Oh beautiful, oh the dearest haramija (robber) of my heart, you still seize ma soul...”, and he generously offers her everything that he has left: “I still have a kašika (spoon), and a cane, and I will give them to you, benum đanum (my sweetheart), let's trade, what else can I give you, if you want I can even give you my kaiš (belt)...”

Devastated with the desire for actual physical contact, at a moment Dervish does not choose words any longer: “Let me be with you, you will not regret it, because you will see what I can do, and I will not stop day or night...” An anonymous transcriber, probably from the 18th century, crossed out these verses and noted on the side: “These verses are scandalous and obscene and therefore should not be read but should rather be deleted.”

Dervish's courtship lasted too long, from one stanza to another he was pierced, wounded, burnt, bleak, sick, tired. He wasted his efforts, he tried everything and at last almost lost his mind. Expectedly, his beloved became his “ćafir dušman (infidel enemy)”: “I no longer yearn for you, you hurt my soul, but I am getting rid of you, you are no longer dear to me, I am going to ask a teptiš (investigation) against you, I am angry Old Dervish”.

The legend goes that Stijepo Đurđević married the rector's daughter to whom Derviš is dedicated. It is very difficult to establish if it is true. He got married twice, and his first wife's name is not known. They married in or about 1624/5. She died soon, and their only son lived for only twenty years. Stijepo's second wife was Mara Gundulić, whom he married in 1631. Mara, Stijepo and their newborn son all died a year later.

Perhaps Đurđević was not inspired by the rector's daughter at all, or she was not his only inspiration. Perhaps he was inspired by dervish poetry, love verses dedicated to God, which were at times ambiguous and explicit despite their sublime purpose. Most literary historians agree that Derviš is a parody of Petrarchan lyric poetry and the birth of the genre of Dubrovnik comic poem. Poet and essayist Nasko Frndić (1920-2011) is one of the few, if not the only one, who considered the possibility of Đurđević's inspiration in dervish poetry. However, the final judgment of this assumption can be given only by experts in the poetry written by dervishes.

Stijepo Đurđević masterfully intertwined characters and speeches of Dubrovnik and Bosnia of the 17th century and actually sang about the timeless wealth of diversity. Since, Derviš was gladly read by his contemporaries and people of later centuries, and the magic of his verses works even today.

The first page of the transcript of poem “Derviš” by Stijepo Giorgi (Đurđević) Giman, 18th century, Library of the Institute for Historical Studies of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik, collection Bizzaro.

Text on page 35 of poem “Derviš” by Stijepo Đurđević, 18th century, Library of the Institute for Historical Studies of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik, collection Bizzaro and transcription of part of the text.

Srce mi se već rastapa

od ljuvene gorke bijede,

Dedo hljeba, ni ćevapa

nelagodan već ne jede

a ti zlom se mojim gojiš

ja sam Dedo lačan Derviš.

Na Mekćemi (76) nit se štuje,

ni već Dedo čorbe (77) kusa,

nit se igra, ni raduje,

neg' se u prsi stijenom lupa,

je da mu se ti umoliš,

pogrđen sam Dedo Derviš.

Plačan Dedo već ne ruča,

niti veće kafu srka,

neg golonog bez papuča

po najvećem snijegu trka,

cječ plamena kjem ga goriš,

razgorjen sam Dedo Derviš.

Samo pijem u noć, i u dan

ljuti šerbet (78) mojeh suza,

er se čujem jôh otrovan

od ljuvenijeh tvojih mahmuza (79),

kjem nadamnom ti gospodiš

izboden sam Dedo Derviš.

Ja bih htio moja draga,

cječ ljubavi tvê jedine,

da mi je čaša tvâ pašmaga (80),

kôm bih činio tebi eškine (81),

da me ovako ne žalostiš

žalostiv sam Dedo Derviš.

..........

76. Mekćeme – Luoco di giustizia

77. čorbe – brodo

78. šerbet – siropo

79. mahmuza – ostroghe

80. pašmage – pianelle

81. eškine (aškine) - brindisi

REFERENCES:

Dervisc Gosp. Stjepa Giorgi Ghimana, manuscript, 18th century, Library of the Institute for Historical Studies of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik, collection Bizzaro.

Vojnović, Lujo (1898), “Zapisci plemenitoga gospara Marina Marojice Kaboge izvanrednoga poslanika Republike Dubrovačke na Carigradskome dvoru“, Belgrade: Spomenik SKA, no. 34.

Kolendić, Petar (1902), “Nešto o Đorđićevoj 'Dervišijadi'“, Dubrovnik: Srđ, list za književnost i nauku, vol. 1.

Pavlović, Dragoljub (1955), “Prilozi biografiji Stijepa Đurđevića“, Belgrade: Zbornik Filozofskog fakulteta, vol. 3.

Pantić, Miroslav (1956), “Još jedan prilog poznavanju Stijepa Đurđevića“, Belgrade: Prilozi za književnosti, jezik, istoriju i folklor, vol. 22.

Pantić, Miroslav (1962), “Rukopisi negdašnje biblioteke Bizaro u Historijskom institutu u Dubrovniku“, Dubrovnik: Anali Historijskog instituta JAZU u Dubrovniku, no. 8-9.

Frndić, Nasko (1993), “Jezični i sadržajni aspekti Đurđevićeva 'Derviša'“, Zagreb: Građa i rasprave o hrvatskoj književnosti i kazalištu, no. 20/1.

Vekarić, Nenad (2014, 2016), Vlastela grada Dubrovnika, Zagreb – Dubrovnik: Institute for Historical Studies of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Dubrovnik, vol. 5 and 7.

Tucaković, Ekrem, “Odlike sufijske poezije“: https://www.bosnianexperience.com/13-tekst-br08-1-1-2tyll-1

Tucaković, Ekrem, “Sufijske ideje u poeziji Bošnjaka na perzijskom jeziku“: https://www.bosnianexperience.com/13-tekst-br03