THE WOMAN IN THE MUSLIM FOLK POETRY

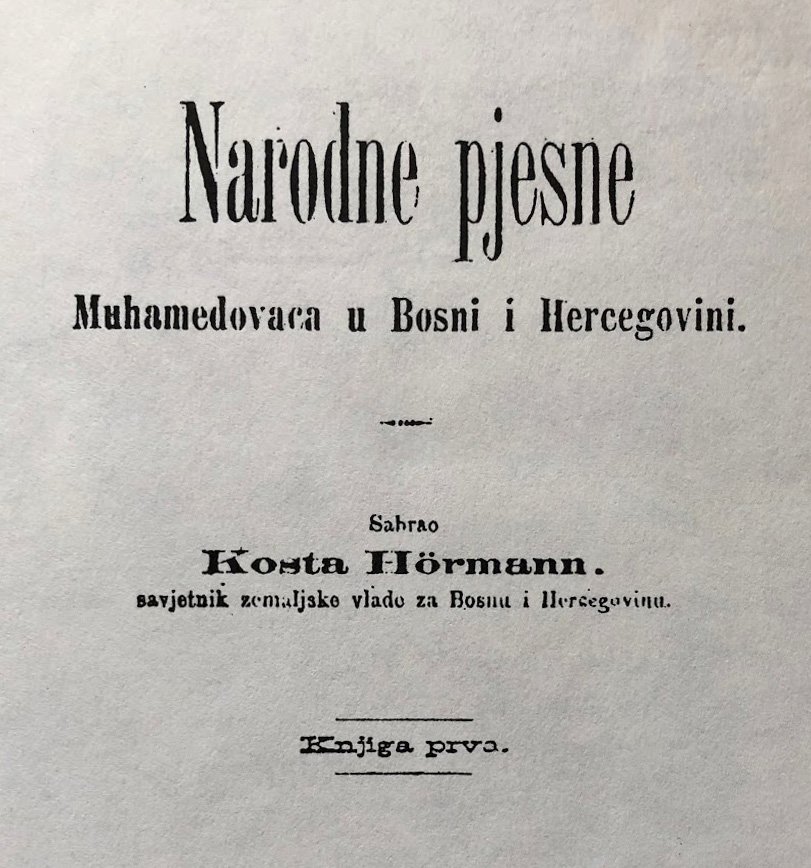

Author: Aziz Kadribegović • Illustration: Kosta Hӧrmann, the first collector and publisher of Muslim folk poems (Narodne pjesme Muhamedovaca u Bosni i Hercegovini (Folk Poems of Mohammedans in Bosnia and Herzegovina), Sarajevo, 1888)

It has been recorded many times that our first folk poems, particularly the heroic or male ones, as they were called, told or sung with the accompaniment of the gusle, were one of the distinctive features of Ramadan evenings, Ramadan get-togethers and gatherings. At the time, in inns or musafirhanas (free lodgings), and particularly in some beys' houses and castles (in the room in the tower!) people used to gather around a chat, coffee and hookah (and a drink or two to be honest) listened, with extraordinary enjoyment and empathy, to a broad spectrum of heroic battles and fights, victories and defeats, fights for honor and honesty, for people and religion, or for the woman and love, all sung by Ramadan singers, favorite guests in every environment and in every house. Later on, the register extended, and besides men songs, women songs fought the place they deserved. These were lyrical songs, full of emotion, softness, yearning and love rapture, full of sevdah and the fine, quaint melody and beauty. The gusle (which have by now almost mysteriously disappeared from Muslim tradition!) were then joined by various kinds of tamburas, as Giljferding wrote in his book Putovanju po Hercegovini, Bosni i staroj Srbiji (A Journey through Herzegovina, Bosnia and old Serbia) (ed. Sarajevo, 1972), the favorite instruments of Bosnian and Herzegovinian Muslims, particularly by saz, which could suitably express and supplement this new poetic sensibility. This is how sevdalinka came into being, a unique kind of lyrical love poem and song “which could vent both the enthusiasm with life and love yearning, as well as Orientally intoned regret for youth, or pain due to the past or unrequited love” (M. Maglajlić). It could also depict the aesthetic feeling which both implies, for instance, the beauty of a guy or a girl, places and towns, waters and parks, and whose refined and subdued sensual color rather speaks of the depth and self-awareness of the attitude toward life and the world it is in. Ramadan evenings thus became inspiration for religious rapture and abundance of prayers, and the basis for a distinctive scenic experience, the beauty of poetic form and evocation of the past, historical, imbued with juices of life and harmony of expression, with all the tones and cadences in which one could recognize the pulses of the being, spirit and breath of a nation, its suffering, joy, rapture, its past and future strength.

The extent of attachment to our poem or song, of its ability to toughen and empower our man and, which is particularly indicative, of how much people identified themselves with it, are confirmed by Safvet-beg Bašagić in his book Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u islamskoj književnosti (Bosniaks and Herzegovinians in Islamic Literature) (Sarajevo, 1912), where he, among other things, wrote the following:

“My father told me, when Turkish parliament first met, that Fehim ef. Đumišić invited all Bosnian and Herzegovinian representatives to dinner. Fehim ef. had heard from somebody that there was, in Istanbul, a Sarajevo lady who was known as a good singer. Without sparing money and effort to organize a true Bosnian dinner for his guests, he brough the singer to his abode to sing several songs for them. Hikmet, sitting at his table, was one of the guests, since there was no joy without akšamluk (dusk-time get-together). Everybody knew of this weakness of his, and nobody minded. My late father said that, while the gusle-player and the singer sang, he watched Hikmet and his mood all the time. He sat still, which was unusual for him, watched seriously and listened to everything with deep respect and childish rapture. Among other songs, the Sarajevo singer began to sing the sevdalinka with the following verses:

Kun' ga, majko, i ja ću ga kleti,

Ali stani, ja ću započeti:

Tamnica mu moja njedra bila itd.

(Curse him, mother, I'll curse him too,

But stop, I will begin:

Let my bosom be his dungeon, etc.)

Having heard them Hikmet jumped up and excitedly shouted: “My people are the greatest poet!”, and then began to explain the beauty of this folk song according to Arabic poetics to those present. Everybody wondered what Hikmet found in this song?!ˮ

In general, the motif of love is one of the prevailing driving motifs of Muslim folk poems, which in turn directly results from the beauty of a person (mostly a woman, but a man as well). And since the woman in general, particularly her beauty, is a frequent topic of world literature and arts, in our folk poems as well the woman is the reason “for which lances break and hero's blood is shed” even for a change of religion itself. Thus, for example, in the poem “Alibeg Atlagić's Daughters” Ivan, a captain from Zadar, fell in love with Sultanija, which had been his captive for three years, and converted to Islam because of her, to be able to stay with his true love.

Ivanu je majka govorila:

“Eto ti je, da bi je ne bilo,

gotov ti je roblje isturčiti.ˮ

U ruci mu alkatmer bijaše,

on istrka na tanahnu kulu,

ona klanja turskoga namaza,

udari je katmerom po lišcu

“Klanjaj brže, draža od očiju!ˮ

(Mother told Ivan:

“Here she is, I wish she weren't,

You shouldn't become a Turk as your slaves.”

He had a carnation in his hand,

And he ran up the lean tower,

She was praying a Turkish prayer,

And he patted her with carnation on the face

“Pray faster, you dearer than the eyes!”)

As claimed by Kosta Hӧrmann, the first collector and publisher of Muslim folk poems (Narodne pjesme Muhamedovaca u Bosni i Hercegovini (Folk Poems of Mohammedans in Bosnia and Herzegovina), Sarajevo, 1888), the woman is “...very decent: She leads a modest life at her home, and it is there that she spins wool, weaves thin cloth, embroiders scarfs and threads pearls. It is their duty to raise children: boys until they grows to carry heroic weapons and begin to fight, and girls until they are old enough to be married. In Mohammedan women we find the same love for the home and the children as we find in other ones. The woman is sanctity to the hero, he will forgive everything, but if you hurt his honor, it's certain that your head will go off. Loyalty of the wife, girl's purity, is the greatest sanctity. However, poems also tell of women with brave hearts; you have Ajkuna, who saves her Alija Alijagić, you have heroine Begija, then Ljubović-bey's daughter, who conquers Baghdad and obtains a pashaluk from the sultan ... The hero respects his mother the most; when she implores him, he will obey her whatever it takes, he will leave his true love and marry without love, he will let his loyal sweetheart go even if his heart breaks of sorrow... Just look at caresses and tenderness between lovers! Flame is burning from some town poems, there's no end to loyalty; everything is full of life and wonderful rapture.”

This rapture would find a unique expression in sevdalinkas, poems and songs about love, which are even more, a poetic magic, a unique expression of the wounded and quivering folk soul, sweet and wistful love yearning of a woman who cannot achieves what she wants due to various circumstances, when she cries and sings at the same time, and everything is condensed in the word sevdah, which implies pain and sadness, sensuality and eroticism, passion and ecstasy, quivering and fainting, simply yearning of the girl's grieving heart for her sweetheart, who is either in the war for someone else's empire or on a journey from which he will 'return or not':

Jesam li ti govorila , dragi:

“Ne ašikuj, ne veži sevdaha!

Od sevdaha goreg jada nema,

ni žalosti od ašikovanja.

Na žalost će i komšija doći,

al za jade niko i ne znade,

osim Boga i sevdaha moga.ˮ

(Haven't I told you, darling:

“Do not court, do not fall into sevdah!

There is no worse misery than sevdah.

Nor worse sorrow than courting.

The neighbor will share your grief when someone dies,

But no one knows of your misery

Except God and my sevdah”)

“By their poetic character, sevdalinkas have, in themselves, some features of the ballad, its darkened tragedy of painful feeling left by a cause or an event. The difference is in that sevdalinka does not have a plot in its development and dynamic flow, but only a subconscious event – an incident, in its full brevity and irrelevance, more as an occasion and summary, which gives rise to what is essential – a love sigh as a fateful lyrical-erotic outcome ˮ, Muhsin Rizvić wrote in his study of the lyrical-psychological structure of sevdalinka. The famous ballad about Hasanaginica introduces the notion of shame, which is the central motif of tragic events and which established a new emotional value in the complex being of the Muslim wife, a value unknown of in the world poetry, which, among other things, thrilled great Goethe and made this wonderful Muslim poem which, with extremely tragic accents, features the entire emotional world of the Muslim woman and the whole drama of her life, known in the whole world and indicate the wealth, drama and complexity of the Muslim being in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Certainly, these are only some points pertaining to our folk poetry which reveal the image of woman, her historical course and the role in crucial life events.