INTIMATE SPACES IN ISLAMIC CULTURE AS MOTIFS OF PAINTERS OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

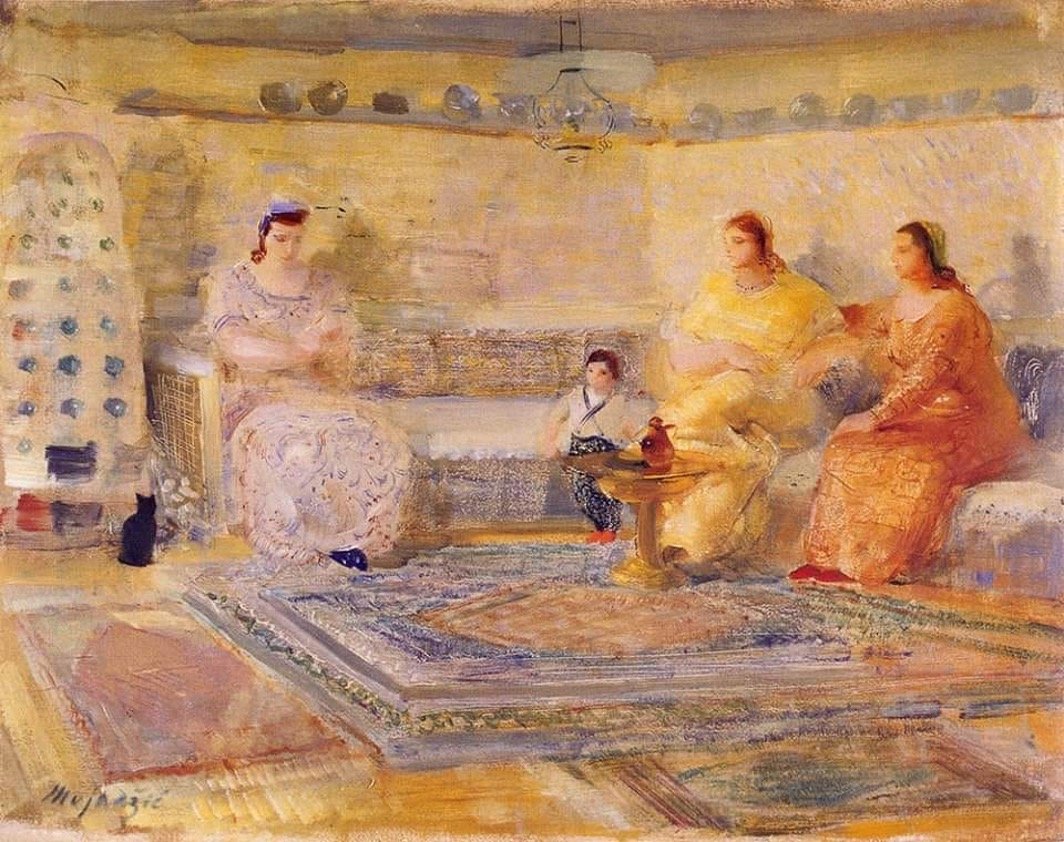

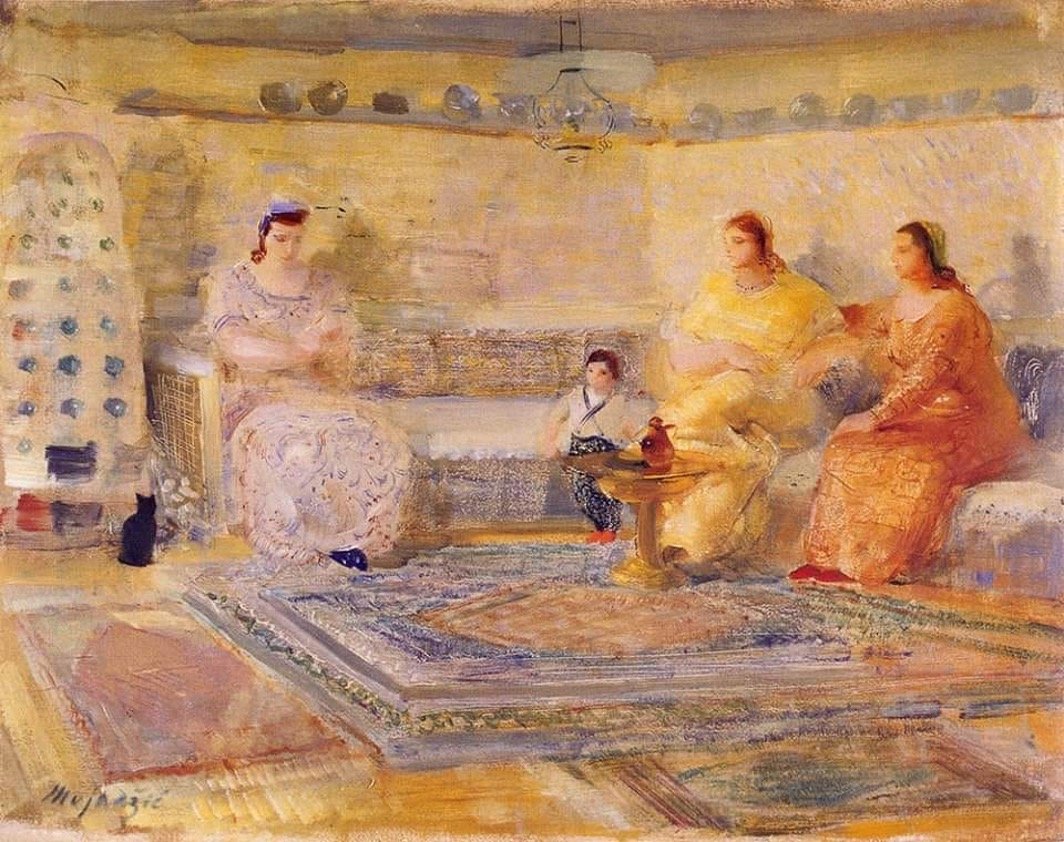

Author: Prof. Aida Abadžić-Hodžić, PhD, Faculty of Philosophy of University of Sarajevo • Illustration: Omer Mujadžić, Bosanska soba, 1939

Some of the most beautiful paintings in the history of modern painting in Bosnia and Herzegovina were created after the motifs from the interior of Muslim houses. These spaces most faithfully depict the high culture of living in Islam: significance of privacy, beauty, harmony, connection with nature and nourishing family ties. Distanced from spaces of market bustle, interiors of Bosnian houses were spaces where tradition was preserved as alive and meaningful and which had their rules of conduct in line with adopted spiritual values. These rooms were full of light and whiteness, covered with filigree embroidery and weave, mastery of woodcarving, without dark and gloomy notes, foreign to Islamic serenity of life. In the harmony of proportions close to human measures, the architecture of the house opened in a gentle and friendly way, while the height of view and horizon was at the level of the person who sits on a sofa or the floor while eating and corresponded to values of the worldview. They are spaces of safety, warmth and firm family ties, and some of the greatest painters of Bosnia and Herzegovina return to them or revive them in their paintings.

When Omer Mujadžić (1903–1991), the youngest student ever admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts and Art Crafts in Zagreb, remembered his Bosanska Gradiška in his extraordinary paintings created between the two wars, his canvases revived moments from his sister's room, full of young women embroidering and mothers playing with children. The rooms are kept warm by means of soft rugs and sofas covered with handiwork.

In his desire to hide from daily life, which was not familiar to him, and striving to preserve a safe and familiar world, Behaudin Selmanović (1915–1972), a student of the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, a painter from the respectable Selmanović family from Pljevlje, painted a series of studies of the interiors of Bosnian house. On these paintings of Selmanović, Islamic tradition uniquely united with modern European painting. Ever since his early youth Selmanović directly learned about the values of Islamic art. He gained the first experiences of the kind in his childhood home, in one of the most beautiful and the oldest traditional houses of the Ottoman period in the area of Pljevlje, which is considered to have been built as early as in the 16th century. Behaudin Selmanović could best learn about the clarity and harmony of proportionate relations in architectural structures of the classical period of Ottoman art in his childhood and in the interior of Husein Pasha Boljanić Mosque in Pljevlje. In the same setting he first encountered the intense colors of interior decoration, complex ornamental forms and expressive values of handwriting of Islamic calligraphy. The powerful colors and motifs from luxurious interior decoration of this mosque were later present on Behaudin's paintings of the interiors of Bosnian houses.

In prominent verticals of Herzegovinian cypresses and in the dignified posture of Bosnian wife while praying, with the head covered with embroidered kerchief Salim Obralić (1945–2018) summarized the arch of his life path, largely spent between his native Maglaj and studio in Počitelj, revealing in the same painting a view of the simplicity of Bosnian room, painted white.

Fragrance of an old book and fruits on the table, murmur of dense treetops which enter through the room window, ticking of the old clock on the table, playful patterns on the rug and mat on the sofa, dancing white curtains on the window frame – all these are incorporated in the fragrances, colors and sound of childhood and remained permanently inscribed in the interior of mother's room, filled with gentleness, warmth and wisdom, on a splendid painting by Safet Zec. No one in the painting of Bosnia and Herzegovina has so subtly sensed and suspended the character of the experienced space in the interior of the house as Safet Zec managed to do – whether on the canvas of Soba moje majke (My mother's room) (1976) or of Kuća moje sestre (My sister's house) (1974), where the minute white cobble of the front yard spreads like a meadow of white flowers, and the space slowly withdraws from the yard, across the balcony to the hidden privacy of the sister's room.