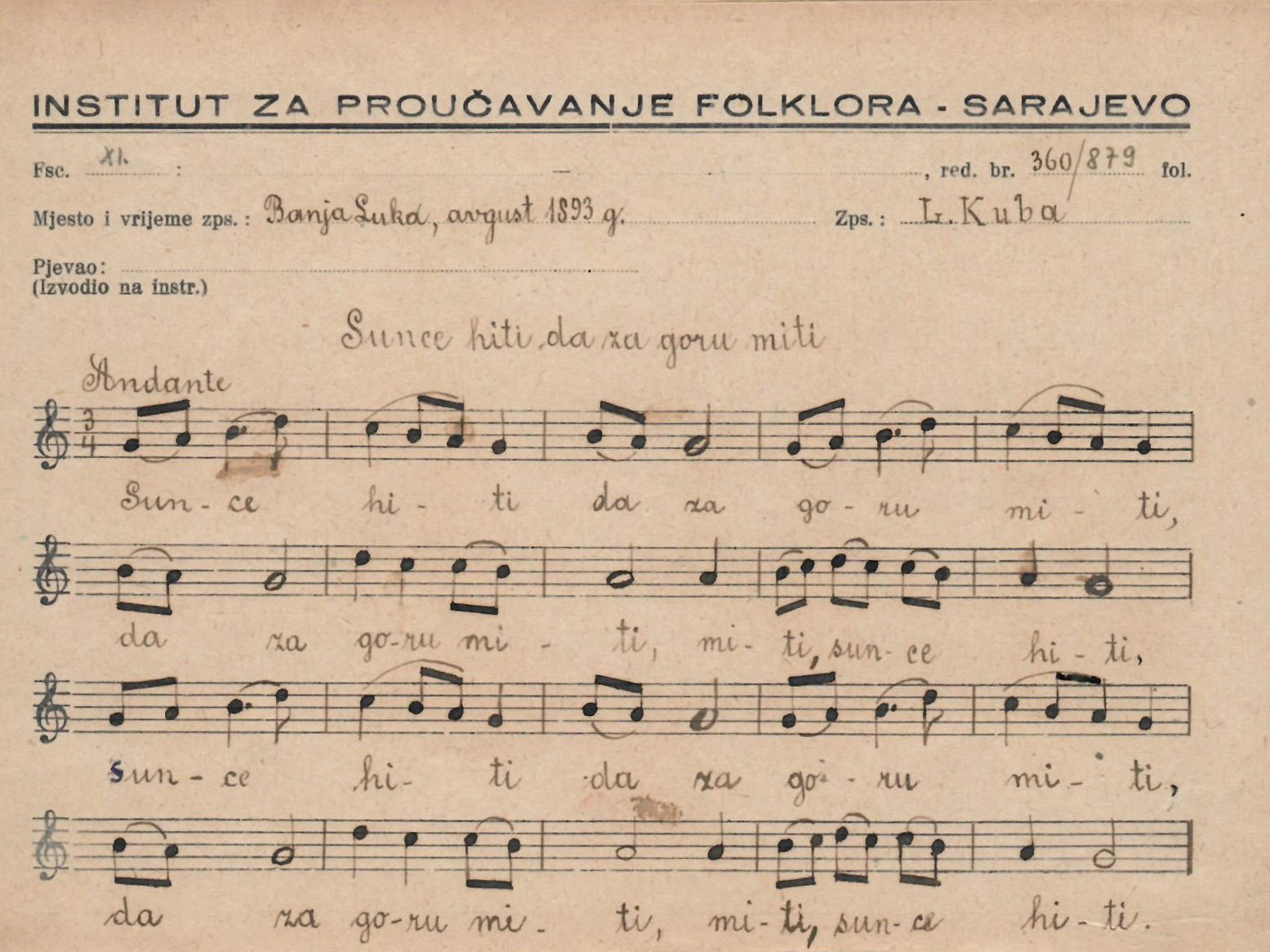

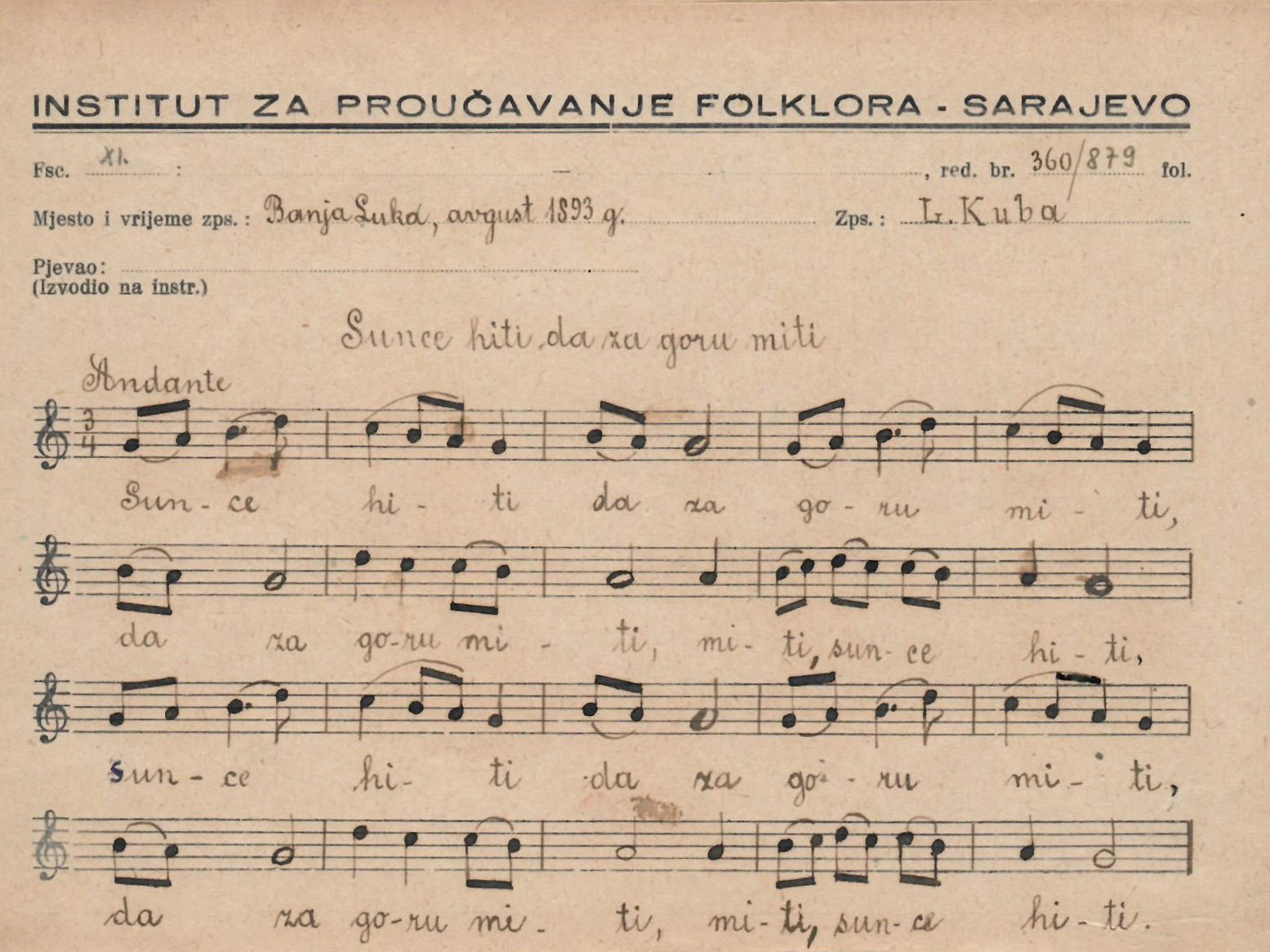

LUDVIK KUBA’S MUSICAL NOTATIONS

Author: Nirha Efendić, PhD, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina • Illustration: Ludvik Kuba’s musical notations from 1893

Czech ethnomusicologist and folk music collector Ludvik Kuba arrived in Bosnia in the summer of 1893, searching for the folk songs of South Slavs. In the period that preceded his arrival in Bosnia, while ethnomusicologically studying the region of Dalmatia and Montenegro, Kuba desired the possibility to record folk materials in Bosnia as well. However, since he was not well informed about the cultural climate in Bosnia and Herzegovina during Austro-Hungarian rule over the region, Kuba believed that the authorities would not be happy about his collecting activities. Still, when he met some fellow countrymen while working in Dalmatia, he was persuaded that he could travel to those regions to record songs.[1] Kuba described this important encounter in a piece entitled Kako sam najzad dospio u Bosnu (How I finally got to Bosnia): “And it happened in 1892, very simply, on a mail boat by which I traveled from Dubrovnik to Metković with the aim to continue my journey to the hinterland of Dalmatia via Vrhgorac. On the narrow deck, it was almost impossible not to meet two of my compatriots and their families, who were returning to Sarajevo from vacation. They were a teacher at the teachers' college, J. Krčmar, and school inspector J. Matela...ˮ[2] Having learned about the reasons for Kuba's earnest desire to come to Bosnia, as well as about his concern for his personal safety during his stay, his fellow countrymen suggested that he come to Sarajevo with them straight away, and that they would introduce him to the then director of the National Museum, a man of Slavic origin, Kosta Hörmann, whom they knew personally. And that's how it went. The meeting with Hörmann exceeded all of Kuba's expectations. As a matter of fact, this high-ranking Austro-Hungarian official was already familiar with Kuba's collecting activity and he saw his arrival as a great opportunity to offer him an engagement which would be of a great benefit to the Museum as well. Describing the details of the contract, Kuba recorded: “We agreed that my travel costs, which Hörmann estimated at 19 krunas a day, would be paid, and that I would travel across Bosnia and Herzegovina according to an agreed schedule, and would submit the collected materials monthly. In the following year (1893) the plan was fulfilled and I collected and submitted 1,125 tunes and lyrics.”[3] Kuba's collecting tour of Bosnia and Herzegovina resulted in a comprehensive collection of about a thousand songs, together with sheet music of their tunes, which were published in the Glasnik (Herald) of the National Museum in Sarajevo from 1906 to 1910.

Explaining the way in which he performed the agreed job, Kuba recorded: “I set forth according to the following schedule: in the first month, I planned to tour the southeast part of Bosnia along with Novi Pazar Sandžak, in the second month to go to Herzegovina, in the third month to tour West Bosnia and in the fourth month I intended to tour Northeast Bosnia. However, I was not able to fulfill the last part of the plan because cholera broke out in that part of the country. I therefore returned and continued to work in Kiseljak and in Sarajevo.”

For the traditional context of the emergence and oral life of sevdalinka, significance is attached to Kuba's description of courting (ašikovanje):

It is true that the Mohammedan bridegroom is not allowed to see the bride until he takes her away, but songs tell us a lot about ašikovanje, i.e. about the falling in love and flirting of young people. We can see it on Fridays when young men, through holes in gates and fences, try to catch a glimpse of the festively dressed girls, who walk around the courtyard or play there. In one song, the parents ask the newly married young woman why she is so mirthless, and she confesses that she cannot forget her first 'ašik', her first love. At the time, a young man could fall in love merely with the girl's name, as confessed by Bakarević Avdaga, who thus speaks to his Mulija: “Whoever gave you such a name, let a dagger stab his heart!”[4]

The output of Kuba's four-month tour of Bosnia and Herzegovina was compiled in a comprehensive collection of over 1,000 different lyrical songs. The total number of songs that were submitted to the administration of the National Museum – along with the musical notation of their tunes – amounted to 1,125 units.

Details of Kuba's arrival in Bosnia can be found in his text entitled Kako sam najzad dospio u Bosnu (How I finally got to Bosnia). Translation from Czech: Bogdan L. Dabić. The Preface to Kuba's book Štivo o Bosni i Hercegovini (A Reading about Bosnia and Herzegovina), the original text of which, in Czech, was published in Prague in 1937. I am grateful to Munib Maglajlić. PhD, who drew my attention to this text and allowed me to use the manuscript of the translation of Kuba's book.

Kuba, Kako sam..., p. 10.

Ibid, pp. 14-15.

L. Kuba, Laska v bosensko-hercegovskih pisnich /Love in the songs of Bosnia and Herzegovina /, in the book Cesty za slovanskou pisni 1885-1929 /Journeys for the Slavic song 1885-1929/, published in Prague in 1953; translation from Czech: Bogdan L. Dabić.