THE MOST PRODUCTIVE BOSNEVI (ALJAMIADO) AUTHOR

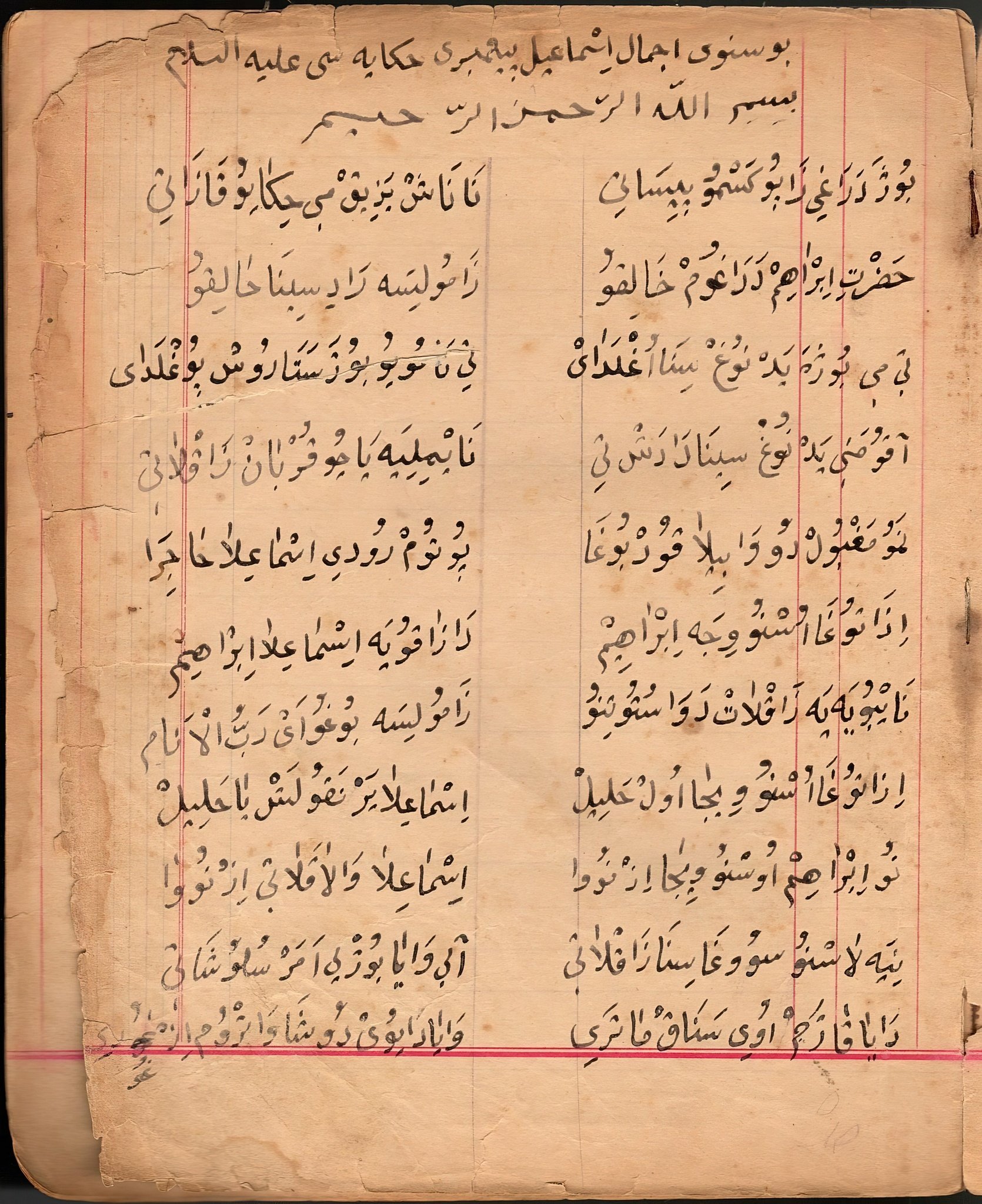

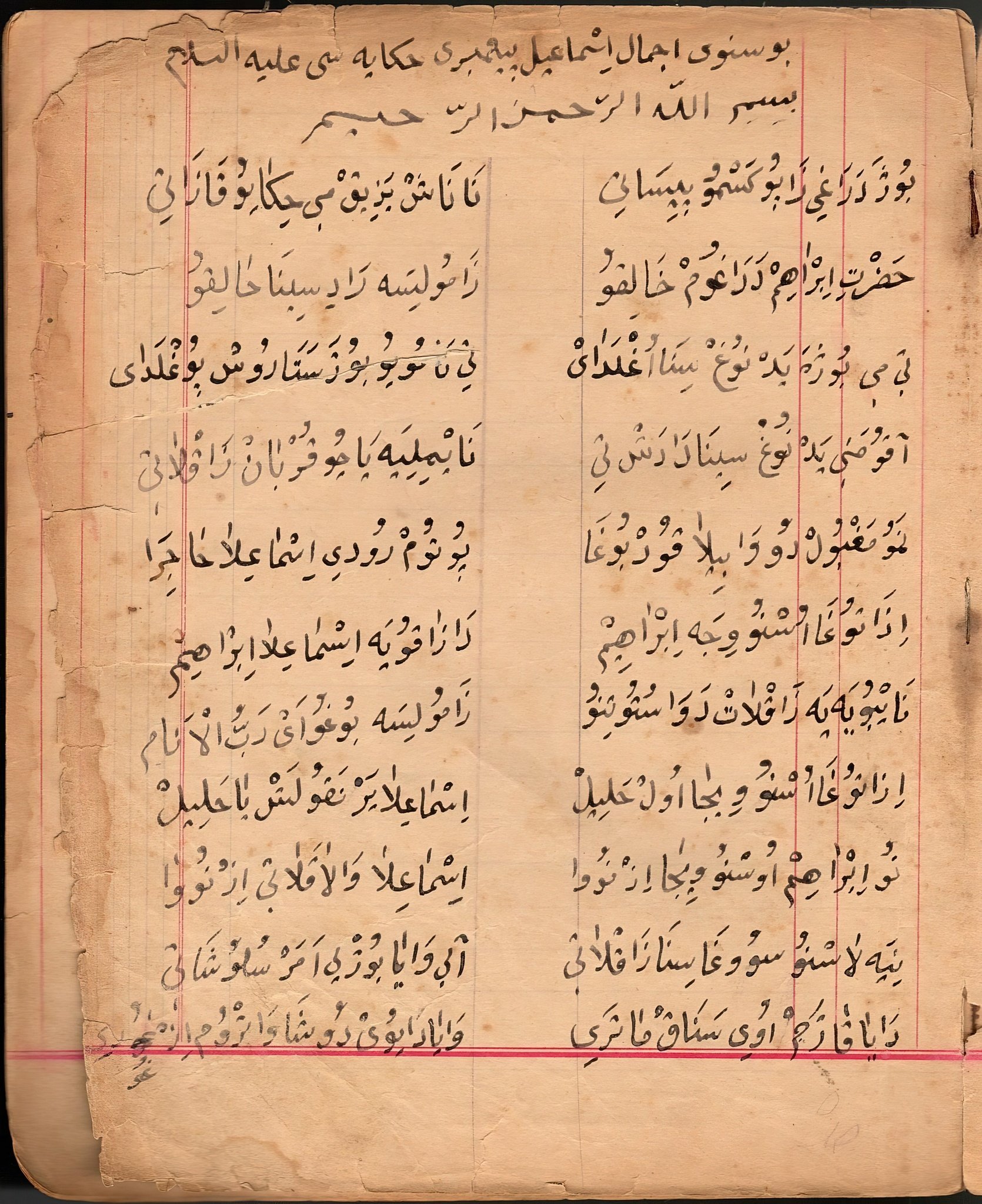

Author: Alen Kalajdžija, PhD, Language Institute in Sarajevo • Illustration: Bosnevi idžmal Ismail pejgamberi hikajesi alejhis-selam

Muharem Dizdarević, a.k.a. Muhamed Rušdi, is a Bosnevi (aljamiado) author from the late 19th and early 20th century. The most comprehensive historical and biographical data about him have been provided by several literary historians (Nametak, 1981: 7-15; Nametak, 1981a; Nametak, 1982; Huković, 1986: 173-176; Huković, 1995) who, for some aspects and data on this author's life, referred to some other available sources (cf. Busuladžić, 1935). By subliming the data from the sources of the described literary history, we will present the necessary information on this important Bosnevi (aljamiado) author.

Muharem Dizdarević, better known under the pen name Muhamed Rušdi (Ruždija) – which, derived from Arabic form Rušdī means “one who takes the right way” (Škaljić, 1979: 537) – drew origin from a famous family from Trebinje, whose forefather was Hasanaga Resulbegović, who was the dizdar (fortress commander) of fortress Banj-Vir in Trebinje from 1718; his descendants were therefore named the Dizdarevićs. Although there are slight disagreements in historiography about the year of this author's birth, it can be concluded that he was born in Trebinje in 1823, or more accurately in 1825. In this town, he first completed Muslim elementary religious school – maktab. He continued his education in Orthodox elementary school – which is an extremely important fact for the time, since it speaks about the scope of education of this Herzegovinian. Later on, he also completed madrasa in Trebinje, where he acquired a sound knowledge of Arabi, Persian and Turkish. Through his office job he was professionally affiliated with official bodies of the Ottoman Bosnia, where he worked for years as a customs officer. Arrival of the Austro-Hungarian authorities in 1878 found him in Trebinje, and he left his job despite the fact that he was very well educated and that he was familiar with three scripts (Arebica, Cyrillic and Latin alphabet) and several languages. Although historiographic data show that many clerks of local origin were transferred from Ottoman to Austro-Hungarian administration, it was not the case with Muhamed Rušdi. It turned out to be very important for the place of this author in the history of Bosniak and BiH literary history. In his fifties, immediately upon leaving the administrative-office job, Rušdi began his life as a poet, and wrote thousands of verses in Bosnian language and Arabic script, on different topics, with different motifs and in different poetic genres. He died in his hometown in 1905, and was buried there at the Gorica cemetery. Today, it is not known if the burial site of this poet has been preserved, and more attention should be paid to this issue in the future.

As has already been mentioned, it was only in his middle age that Rušdi began to write Bosnevi (aljamiado) literature, where he left an immeasurable trace in the development and the overall aesthetic and poetic completion of this kind of literary creations in Bosnian at its twillight. Both Nametak (1981: 9-15) and Huković (1986: 174-175) noted that Rušdi left behind two collections of poems – one on 91 pages of two-column text, which is autographic and which was written, transcribed and bound by the author himself (and which was, by the way, owned by Alija Nametak), and the other one, which consists of 55 pages, 48 of which with two-column and seven of one-column text, which used to be kept at the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the destiny of which after the aggression on Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1995) is virtually unknown. Besides, M. Busuladžić (1935) noted that there was a Rušdi's collection of 156 pages, which was kept at the author's grandson, and which, unfortunately, has not been found until this day.

With respect to works by Muhamed Dizdarević, based on the two available collections, Nametak (1981: 12-13) provided a list of all of his preserved authorial manuscripts of poetic type in Bosnian, which does not include Rušdi's transcriptions of poems by other authors, texts in Arabic and Turkish, and prose texts in Bosnian. This productive author wrote almost 40 poems, from short poems of only several bejts (distichs), e.g. six 15-syllable distichs, to long ones, such as Mevludi-šerif of 210 11-syllable bejts. Although he listed exactly 37 poems, in a section of his monograph which includes transcription of poems Nametak (1981: 179-184) presents a poem of 71 bejts entitled “Nasihatul hukema li Iskenderi Zul-karnejniˮ, which is not included in the list of poems by Muhamed Rušdi, but which is found in Hrestomatija alhamijado književnosti (Nametak, 1981a: 272-280).

Besides the fact that he wrote Bosnian language in Arebica script, in 1943 the First Muslim publishing bookstore owned by Muhamed Bekir Kalajdžić in Mostar published Rušdi's poem Ibrahim alejhisselam, pobožni spjev za muslimansku mladež, which is composed of 574 bejts, in Latin alphabet. Later on, long poems by this author were printed transcribed in Latin alphabet several times.

One can observe that the metric form of hendecasyllable prevails in Rušdi's poems. He used the 15-syllable verse far less often, and wrote a short poem in the 13-syllable and 14-syllable verse respectively. Nametak (1981: 24) also noted that by his oeuvre, Rušdi was very innovative, which is confirmed by the topics he dealt with in his literary discourse – from mawluds, rhymed short stories (hićajas), devout and didactic poems, short poems on various “Islamic topics”, all the way to a special kind which Rushdi specially elaborated – the poem/ narration on God's messengers and selected ones – about Ejub, a.s., Jusuf, a.s., Ibrahim, a.s., h. Fatima, h. Zul-Karnejn. Nametak (1981: 29) provides interesting data that Otto F. Babler published two Rušdi's poems translated into Czech in a collection of important ethnological publications of Slavic literatures entitled Dvě mohamedanske biblicke basne in 1934, whereby Bosniak literary- linguistic practice was presented to this part of Slavic world. An interesting curiosity in poetic creation is also the fact that Rušdi translated some poems, as is explicitly mentioned in a poem about messenger Ejub: “I started from Turkish/ and brought it to Bosnian language”. In this respect, it is interesting that Rušdi gave titles of many of his poems in Turkish, although one can also easily notice the fact that Rušdi called his language only Bosnian, as he pointed out in very titles of his poems: Priča na bosanskom o bagdatskoj gospođi (A story about Baghdan lady in Bosnian) ; Mevludi-šerif bi lisani bosnevi Bosnevi; Bosnevi idžmala Ismail pejgamber hikajesi; Bosnevi lisan ile ahlaki Resulullah; Bosnevi fakirluge sebeb; Bosnevi ilahi Bosnevi Jusuf a.s. hićaja etc. (Nametak, 1981: 12-13).

Without any doubt, it can be claimed that based on the number of presented bejts in the available collections, Rušdi is the most productive Bosnevi poet, though at the twilight of this literary kind. When long poems about h. Zul-Karnejn and Ibrahim a.s. are added to this number, the number exceeds 2,000 bejts, not counting works which have, unfortunately, not been preserved and which can be assumed to have existed, at least in some variants of the already existing preserved poems.

References:

Busuladžić, Mustafa (1935), “Muhamed Rušdi”, Glasnik Vrhovnog straješinstva Islamske vjerske zajednice, year III, Beograd.

Huković, Muhamed (1986), Alhamijado književnost i njeni stvaraoci, Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

Huković, Muhamed (1995), Zbornik alhamijado književnosti, BZK “Preporod”, Sarajevo.

Nametak, Abdurahman (1981), Muhamed Rušdi. Monografija i tekstovi, Starješinstvo Islamske zajednice u SR Bosni i Hercegovini, Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji.

Nametak, Abdurahman (1981a), Hrestomatija bosanske alhamijado književnosti, Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

Nametak, Abdurahman (1982), “Muhamed Rušdi”, Anali Gazi Husrev-begove biblioteke, vol. VII–VIII, Sarajevo.