ABDULVEHAB ILHAMIJA:

A FAMOUS BOSNIAN POET, REBEL AND EVLIJA (A RIGHTEOUS PERSON)

Author: Alen Kalajdžija, PhD, Language Institute in Sarajevo • Illustration: Ilhamija's turbe (grave) in Travnik • Photo: Mirza Hasanefendić

One of the probably best-known Bosnian Aljamiado literature authors is Abdulvehab Ilhamija (1773-1821).

His full name is sejjid šejh el-hadž Abdulvehab ibn Abdulvehab Žepčevi Bosnevi Ilhami-baba. Titula sejjida, which in Arabic otherwise means ‘a gentleman’, and refers to his vonnection, by origin, with Prophet Muhammed, a.s., though researchers point out that it is actually a case of spiritual descendancy rather than blood relationship. He obtained the title of sheikh in Tešanj in 1810, when he became the spiritual guide of Naqshbandi order, which in turn ensured him the title of ‘baba’, which is granted in dervish tradition. He obtained the title of haji when he went for a pilgrimage to Mekka. He was named Abdulvehab after his father. Ilhamija used the Arabized nickname Žepčevi to underscore his Bosnian origin – from Žepče, same as he used the penname Bosnevi, which is also an Arabized form of an ethnic attribute which refers to his Bosnian origin; thus, Bosnevi actually means a Bosniak or a Bosnian. Ilhami, or Ilhamija, is a poetic penname derived from Arabic word 'ilham', which means 'inspiration’, and it is a name he gave to himself and recorded in many poems.

There are many important data about him in the available historical sources and Ilhamija's works themselves. He was born in Žepče in 1773. He died a violent death, by strangulation, in Travnik in 1821, at the age of (as is stated in the content of the chronogram on his grave). As a child, he was an orphan; his father, after whom he was named Abdulvehab, died before he was born, as he says in his poem Bogu fala, Koji čuje (Thanks God, who hears): “Majke nejmam, a pedera (perz. izraz za oznaku oca) ne pamtim, / Što sam fakir i sirota, ne velim.. (I don't have mother, and I don't remember my father, / I don't complain about being poor).” At a point, Ilhamija got married and had three sons: Muhamed, Emin and Halil, whose names are listed in his work Tuhfetul-masallin ve zubdetul-haši'in, which he wrote at the age of 30, at the time when he had terrible headaches and therefore believed that he would die. It is not known whether Ilhamija had more children after that time. With respect to his marriage, Ottoman sources which explain Ilhamija's “straying” say that Ilhamija is married with a melek (angel) girl, who bore him three sons.

He was educated before the famous hodja Ahmed-efendija Karahodža, by all accounts, son of Abdullah Karahodža, who wrote the Bosnian Aljamiado poem Bošnjakuša, in Žepče in 1153 Hijra year, or 1740/1741 A.D. It can be assumed that Ilhamija was under a strong intellectual influence of his teacher, who in Bošnjakuša wrote about numerous deviations of Muslim society of the time. It is also known that Ahmed Karahodža was the imam of Žepče mosque Ferhadija, and from historical sources we also learn that Ilhamija was also the imam of the mosque. Besides, historical sources mention the name of hadji Hadžićerimović, and claim that he also was Ilhamija's teacher. It is not completely clear whether Hadžićerimović was actually Ahmed Karahodža, though it can be assumed that they were two different individuals. During his life, Ilhamija committed himself to education and studying theological sciences, and was oriented toward Sufi studies of Islam. It was for this reason that he first acquired sound knowledge in the field of tasawwuf in Bosnian centers of Sufi spirituality of the time – in Fojnica tekkes in Vukeljići and Oglavak, before sheikh Husein-babo Sikirić and possibly sheikh Abdurahman Sirrija. At the time, Ilhamija completed his religious progress in Tešanj, where he was granted the sheikh idžazetnama, i.e. the permit to lead a dervish oder, by Abdullah-ef. Čankari in 1810.

What has been particularly dealt with in historiography which synthetized the life and work of this author is the issue of his death and the reason for his execution. It is known with certainty that Ilhamija was strangled in vizier Travnik and that his execution was ordered by governor Dželaludin-pasha, better known by the name of Dželal-pasha or Dželalija. Indeed, in 1820, sultan Mahmud II appointed Dželal-pasha governor of Bosnia and gave him very wide powers in establishing order. Upon his arrival, Ilhamija wrote very favorably about him, hoping that the new governor would solve numerous problems of Bosnian society. As the situation actually became even more complicated upon his arrival, Ilhamija proceeded with acerbic critical analyses in his works, and possibly in his activity as the imam, describing anomalies of authorities and society. Allegedly, Dželal-pasha therefore asked him to renounce his criticism expressed in the poem Čudan zeman nastade (A weird time set in). Since Ilhamija did not renounce his views, Dželal-pasha ordered his execution without carrying out the proper procedure. The report that Dželal-pasha sent to Istanbul about Ilhamija's execution lists several reasons which justify such an action, primarily “straying” in belief, since Ilhamija presented himself as an evlija who sees the future, who claimed that he had married a melek-girl, and who knew that rebellions in Bosnia would succeed. All these quasi-facts listed in the report were actually only an excuse for a vain ruler who took meting out justice in his own hands.

At the time when Ilhamija was murdered and later on, legends appeared which ensured “immortality” for Ilhamija and memory of his sacrifice. Thus, it was told that Ilhamija cursed Dželalija, saying that he would not die easily, that Dželalija would not be visited by any important visitors (alluding to dogs), that Ilhamija would remain admired after his death, and that a treatment center would be built at the place of his burial (which is now actually Travnik hospital, built at the spot where Ilhamija was buried). On his grave, the content was written which, in translation, goes as follows: „He is forever alive. / At the moment when he passed to eternity, / His friends remained in grief. / He opened the door of God's mercy and heavenly garden for himself. / And there was nobody like him at his time. / He was maliciously blamed by many liars. / When his tender life was nearing the end, / He drank a deadly glass of Kevser. / And died a martyr's death / Sejjid hadži šejh Vehhab.“

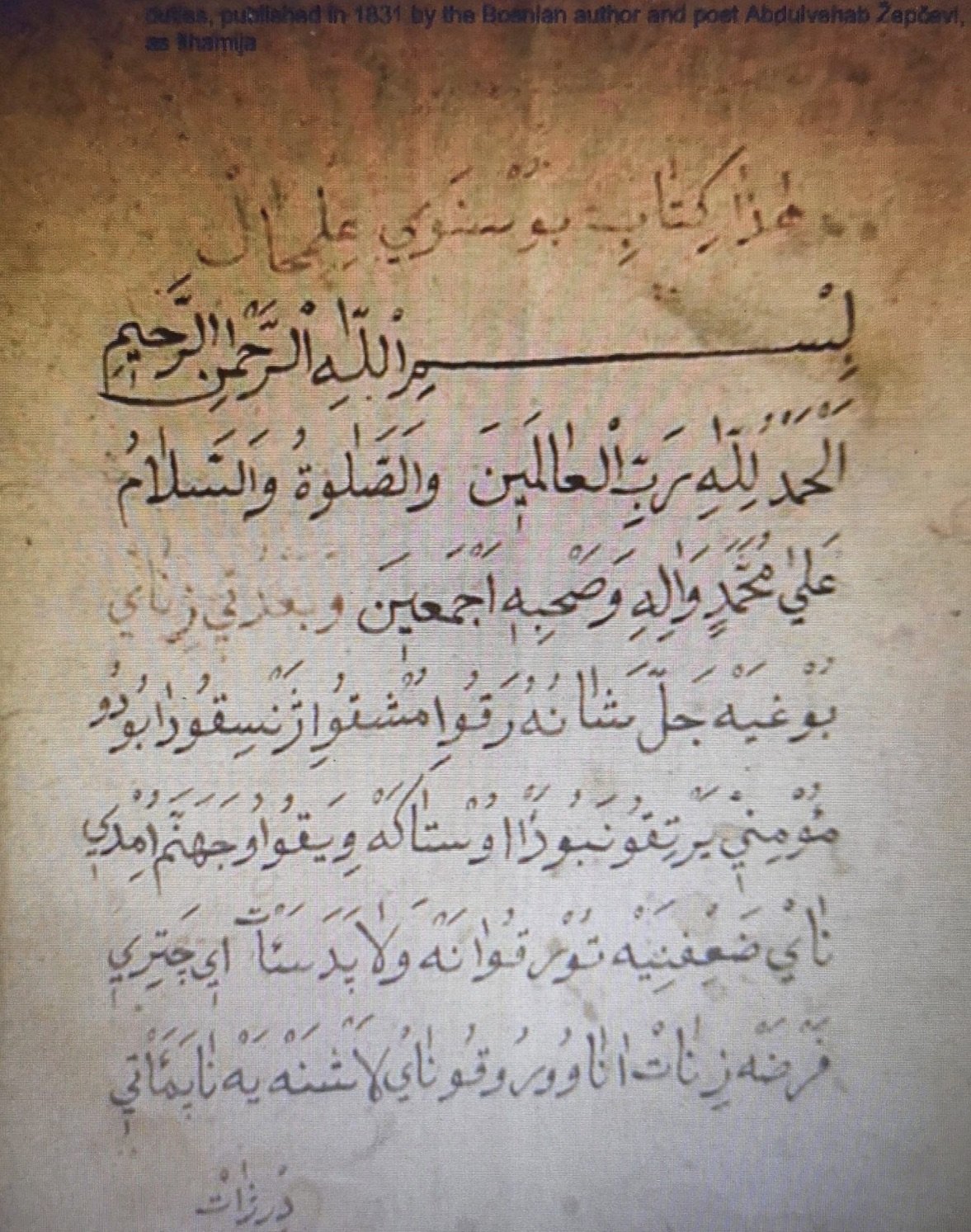

In our history of literature and culture Ilhamija is particularly important by writing works of different nature. He wrote several poems in Arabic and almost 40 poems in Turkish, as well as a theological treatise in Turkish entitled Tuhfetul-musallin ve zubdetul-haši'in. What is particularly important are his works that he wrote in Bosnian. Thus, Ilhamija wrote about 20 poems in Bosnian (some of which are still sung in Bosnian tekkes) and though researchers do not agree about all of them, the following ones are known with certainty: Boga traži i plači; Dervišluk je čadan rahat; Hajat dok me orakme; Ako pitaš za derviše opeta; Ja upitah svog Ja-sina; Bogu fala, Koji čuje; Potlje Boga, ne miluj; Aškom neka gore ašiki; Srce moje, da ti kažem; Džennet saraj, đuzel kuća; Sve je dušman potlje Tebe; Ja upitah svoje duše; Šejhom iršad tko ne najđe; Đe li ti je Halil-paša; Čudan zeman nastade; Ti bresposlen nemoj hodat; Der ti, ašik, hajde Dostu while researchers do not agree about poems Hajde, sinak, te uči and Ti ne hodaj bresposlen, although there are several more which are disputable in terms of Ilhamija's authorship. His poems in Bosnian can be found in different transcripts and manuscript versions of different origins. Thus, it is now known that Ilhamija wrote Ilmihal (textbook for religious instruction) in Bosnian, which is kept in four transcripts, one of which begins with the following words: Haza kitabu bosnevi ilmihal (This book is Bosnian Ilmihal). We already mentioned his work Tuhfetul-musallin ve zubdetul-haši'in, which he wrote in Turkish, but which includes somewhat more than 20 sentences in Bosnian which are, in Ilhamija's opinion, the so-called elfazi-kufr, i.e. blasphemous words and sentences that can banish one from the religion.

Thus, sejjid šejh el-hadž Abdulvehab ibn Abdulvehab Žepčevi Bosnevi Ilhami-baba is an important personality from the history of Bosnian culture, literature and language. His value can be particularly understood from the historical distance which secured him a permanent place in Bosniak and Bosnian and Herzegovinian culture:

„Ja upitah svoje duše: / Kaži mi se tko si ti? / Ona veli: Der pogledaj / Moj saltanet u sebi. / Dva su šaha i dva tahta / Ja sve sudim po sebi. / Dva ćehaja i dva svita / Vas je hućum na meni! (I asked my soul: / Tell me, who are you? / And it said: Please, look at / my magnificence inside you. / There are two shahs and two tahts / I judge everything by myself. / Two masters and two worlds / I am judging you) “

References:

Aksoy, Ȍmer (2019), „Pogubljenje Abdulvehaba Ilhamije u svjetlu novih izvora“, Istraživanja, časopis Fakulteta humanističkih nauka Univerziteta „Džemal Bijedić“, no. 14/2019, Mostar.

Dobrača, Kasim (1974), „Tuhfetul-musallin ve zubdetul-haši'in od Abdul-Vehaba Žepčevije Ihamije“, Anali Gazi Husrev-begove biblioteke, Volume II–III, Sarajevo.

Duranović, Elvir (2017), „Alhamijado Ilmihal Abdulvehhaba Ilhamije Žepčaka“, Anali Gazi Husrev-begove biblioteke, vol. XXXVIII, Sarajevo.

Hadžijamaković, Muhamed (1991), Ilhamija: život i djelo, Sarajevo: Mešihat Islamske zajednice Bosne i Hercegovine, El-Kalem.

Nametak, Abdurahman (1981), Hrestomatija bosanske alhamijado književnosti, Sarajevo: Svjetlost.

Kemura, Sejfudin, Ćorović, Vladimir (1912), Das Serbokroatische Dichtunger bosnischer Moslims aus dem XVII., XVIII. und XIX. Jahrhundert, Zur Kunde der Balkanhalbinsel, II, Quellen und Forschungen, Sarajevo.

Ždralović, Muhamed (1985), „Abdulvehab ibni Abdulvehab Žepčevi – Bosnevi [Ilhamija]“, Anali Gazi Husrev-begove biblioteke V–VI, Sarajevo, 127–144.