KILIMS OF SARAJEVO WORKSHOP AND

THEIR DERIVATIVES

Author: Fatima Kadić-Žutić, PhD, Faculty of Islamic Studies of University of Sarajevo • Photo: Exhibition pavilion of Sarajevo Weaving in Paris, 1899, František Topič

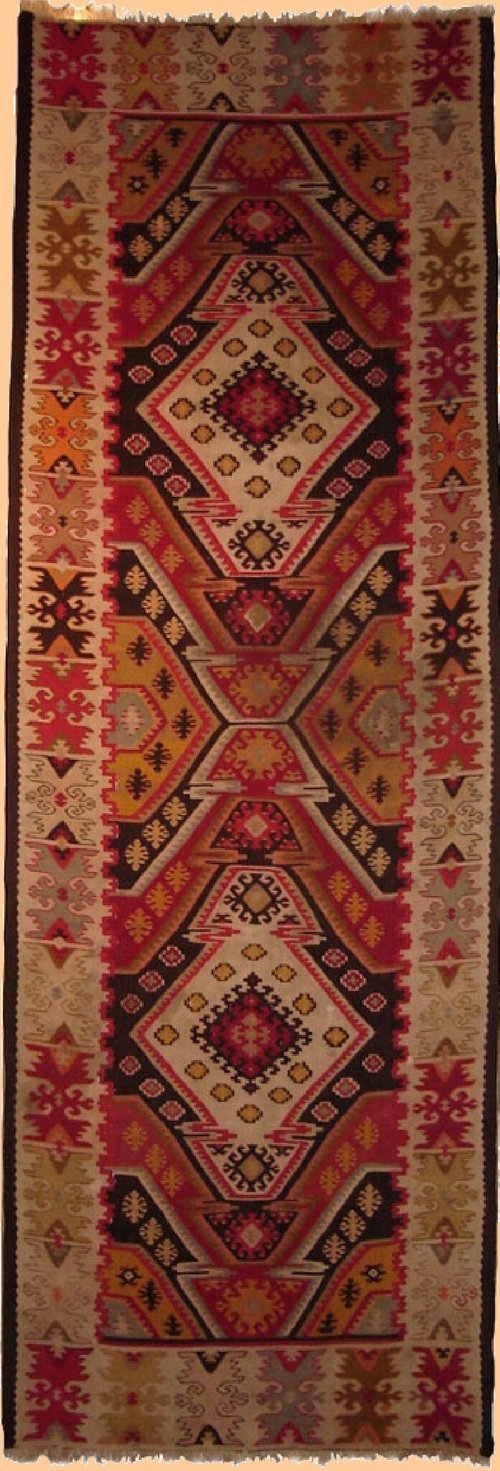

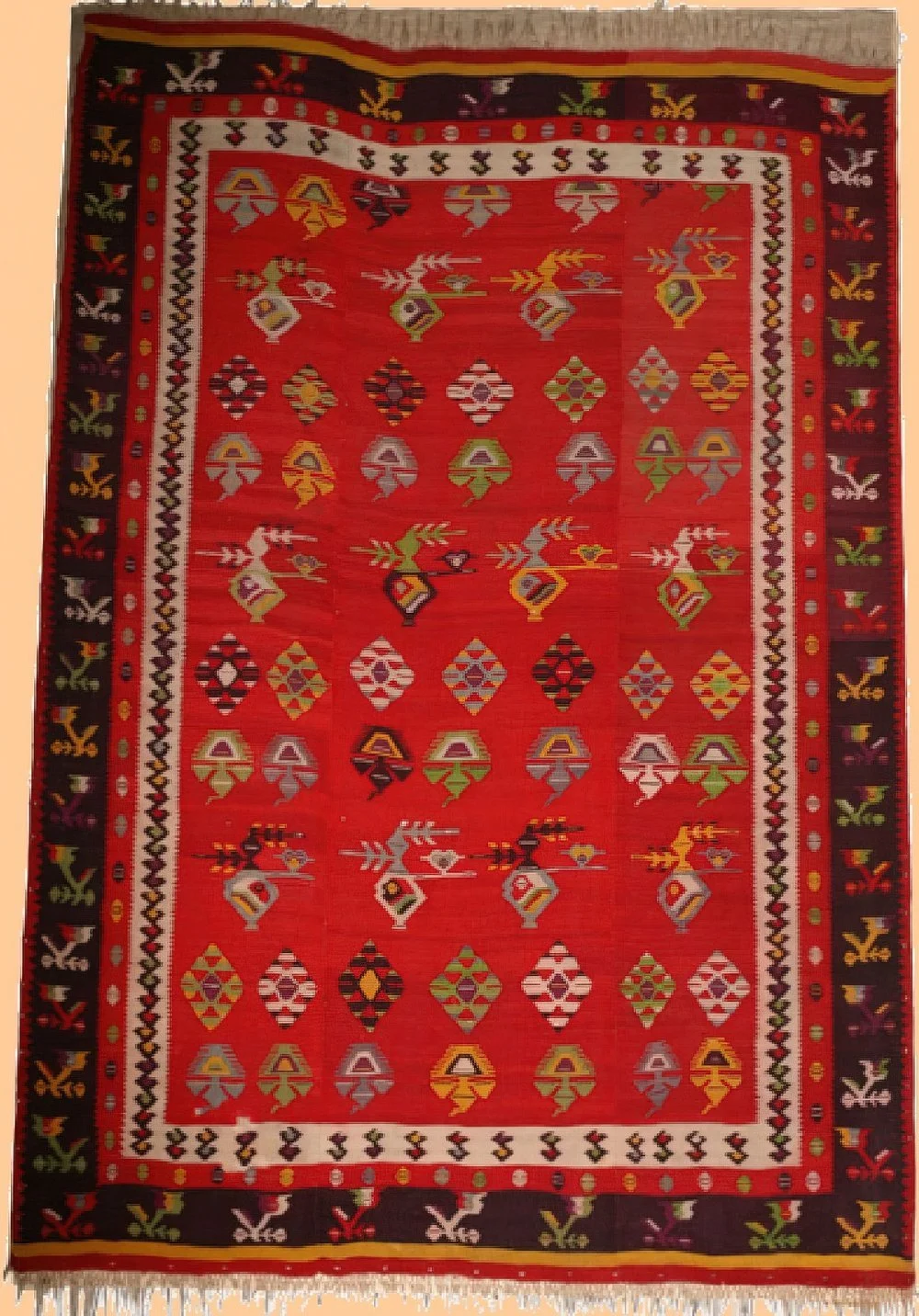

The second stage of making the Bosnian kilim is the kilim woven in the Sarajevo Workshop after 1879 (Figures 4, 6, 8, 13). One cannot say that it was an entirely new type of Bosnian kilim. For example, the sample based on which one of the first templates for the Workshop was made was exactly a Bosnian kilim from the 19th century with the lokumli (lozenges) pattern, which is held in the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Figure 3). Upon the establishment of the Workshop, a campaign of collecting samples was carried out across Bosnian villages and cities, as well as in surrounding areas. Based on these samples, standardized templates, the so-called pattern cards for the Workshop were made (Figures 5, 7, 9). Permanent shades of aniline dyes and a certain quality of yarn were also introduced. Some of these templates have been preserved; however, as Bratislava Vladić-Krstić wrote: “the entire collection of designs is in a very disorganized state, many samples have disappeared and many of them have been lost” (Vladić-Krstić, 1978).

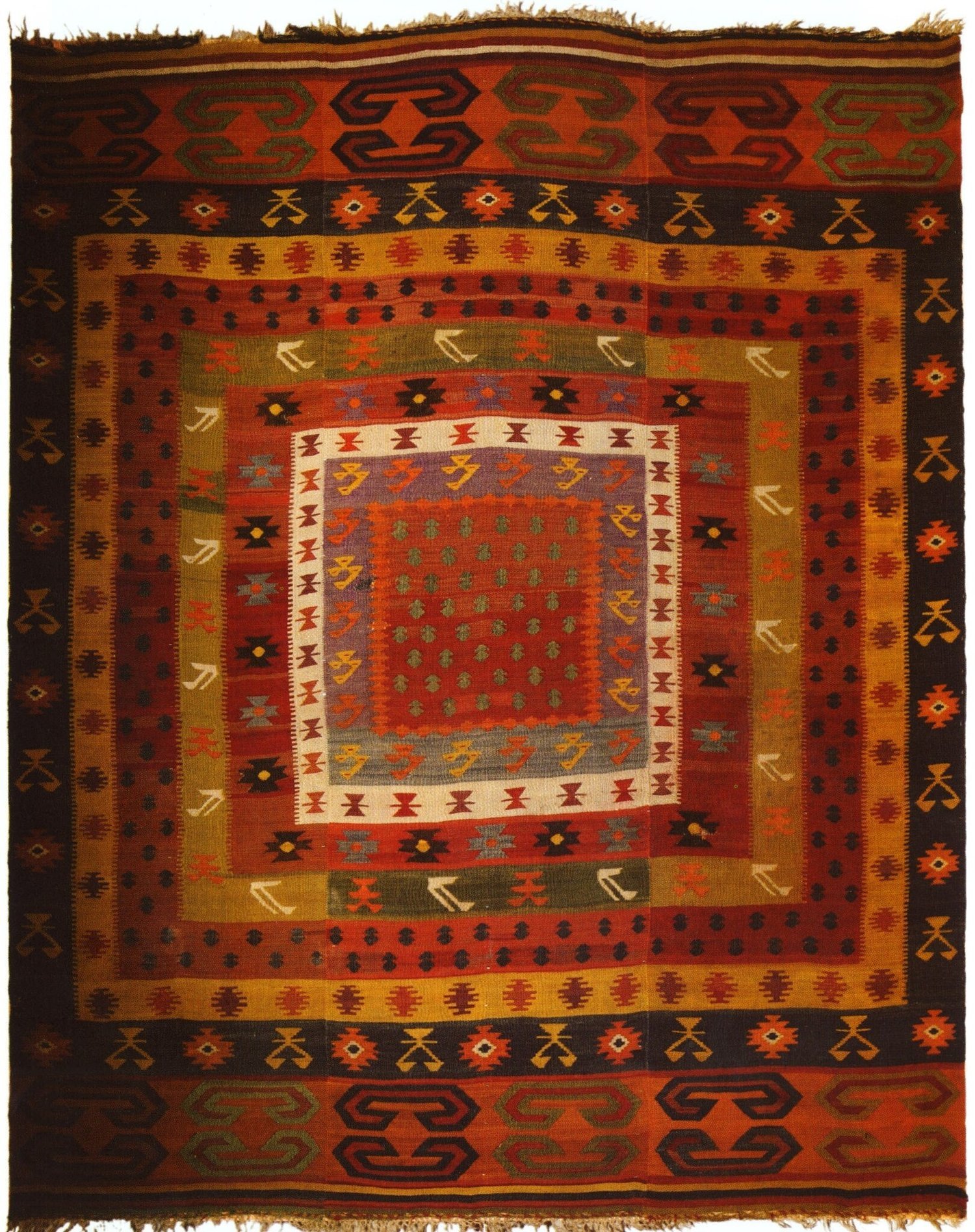

As we have already mentioned, the Kilim/Carpet Workshop also collected samples of Pirot kilims and catalogues of world exhibitions, and faithfully copied designs of carpets made in other world weaving centers and woven in the Sarajevo Workshop (Papić, 1979). The illustrative examples include the pattern of the so-called Transylvanian knotted-pile sajjadas (prayer rugs), which were copied in the Sarajevo Workshop using the slit-tapestry weaving technique (Figures 9, 10). Having in mind the significance of the so-called Transylvanian carpets and sajjadas for the entire research of the Anatolian knotted-pile carpets, these tapestry pieces from Sarajevo are unique examples of the evolution of their patterns. The fact that they are about a hundred years old gives them the status of antiques and a particular value. It should be noted that Bosnian workshop kilim was made according to an accurately established pattern with a broad palette of aniline dyes (including the previously rare blue color, which was intended to satisfy Western taste). These kilims were woven on the vertical loom or the improved horizontal loom, exclusively of imported wool, since wool obtained from Bosnian coarse-fleece (gruboruna) sheep is of poor quality. This cultured workshop kilim lost the iridescence of warm pastel nuances obtained by hand dyeing of wool with vegetable dyestuff, and the charm of slight irregularities which the weaver incorporated in the pattern working without a previously defined template, copying from another kilim or working from memory.

The third stage of the Bosnian kilim emerged when Workshop patterns slowly began to take primacy even in homemade kilim weaving (Figures 11, 12). The Workshop produced pattern cards in the size of a matchbox or a postcard and they could be ordered by mail. Depending on the weaver's skill, these kilims could be made better or worse. When a sample once began to circulate among weavers, they would preserve its basic pattern but change additional motifs as well as colors, which again provided kilims with a degree of originality. They all had one or more borders. As we said before, folk weavers named these patterns after what they reminded them of: bešikaš (a cradle), kandiljaš (a lamp), lalaš (a tulip) (Figure 12) etc. In this stage of Bosnian kilim, patterns u zatke (stripped), zig-zag and na kola (with lozenges) were woven only in villages. By the outbreak of the Second World War, use of natural dyestuff was quickly abandoned. Aniline dyes appeared in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the mid-19th century, but people partly used vegetable dyes until the second half of the 20th century, mostly brown and yellow shades. Weavers of home-made kilims began to use the vertical and the improved horizontal loom, which allowed them to make one-piece kilims.

As we can see, the Austro-Hungarian period marked a turning point in the development of weaving home-made kilims, in terms of design, weaving devices and materials. The third type of Bosnian kilim would reach the climax in the period between the two wars and after them. Weaving this type of kilims was the most intensive in Bosanski Petrovac and Bjelaj. For example, one of the best-known patterns of Bosnian kilim of this period is a pattern which was called Sarajevo zilija in Petrovac, since it first began to be woven after the template from the Sarajevo Workshop (Figure 13). (The term zilija probably reached Bosnia by means of catalogues which the Workshop collected at world exhibitions. The term zili or zilu refers to a special type of tapestry weaving with extra-weft floating (Belkis Acar, 1983).) In other places, on the other hand, this kilim was called Petrovac zilija or na kola (with lozenges). A pattern known under different names: sitni vez (minute weaving), na fesove (with fezes), na saksije (with flowerpots), rašićevac (of the Rašić family) was also copied (Figure 4). One of the most frequent designs of this, third type of Bosnian kilim is the so-called smirjanska šara (Smirna design) (after the name for present Izmir – Smirna), which was also called sandučar (with chests), u kanice (with belts), and sometimes Pirot as well (Figure 8).

Since the second half of the 20th century, weaving kilims with the stylized Baroque design became widespread; in Bosnia-Herzegovina, it appeared under the influence of Vojvodina, west Serbia and Sandžak (Figure 14). In Banat and Chiprovtsi, these floral patterns began to be woven as early as in about 1900, under the influence of patterns from fashion magazines, wallpapers and decorative oil paper.

Carpet from Sarajevo, 20th century, Vrbanjuša Mosque, Sarajevo

The pattern itself is not a sufficient indicator based on which we can say that a kilim is Bosnian. Bosnian kilim can be defined as recognizable compared to its listed Balkan counterparts only by means of the analysis of materials it was woven of, weaving technique and dyestuffs, which is a job that remains to be done. The fact that it shares its patterns with its neighbors by no means diminishes its singularity, value and beauty. On the contrary, Bosnian kilim is only one of the many expressions of tapestry-weaving technique which can be found along the entire “rug-belt”, from the Balkans to Central Asia.

References:

Balpınar Acar, Belkis, Kilim – cicim – zili – sumak, Eren Yayınları, İstanbul, 1983.

Eiland, Murray, Jr., “The Goddess from Anatoliaˮ, Oriental Rug Review, X, 6, Meredith, NH, 1990, pp. 19-26.

Filipović, Marica, Bosanskohercegovački ćilimi iz zbirke Zemaljskog muzeja BiH, Zemaljski muzej BiH, Sarajevo, 2006.

Papić, Radivoje, “Osnivanje i razvoj tkaonice ćilima u Sarajevu (1879-1979)ˮ, 100 godina Tkaonice ćilima u Sarajevu, Tkaonica ćilima Sarajevo – Ilidža, Sarajevo, 1979, pp. 19-22.

Vladić-Krstić, Bratislava, “Ćilimarstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini, prilog proučavanju starih tkanja u Bosni i Hercegovini”, Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja u Sarajevu: etnologija, New series, XXXII, Sarajevo, 1977, pp. 225-296.