DIVERSITY

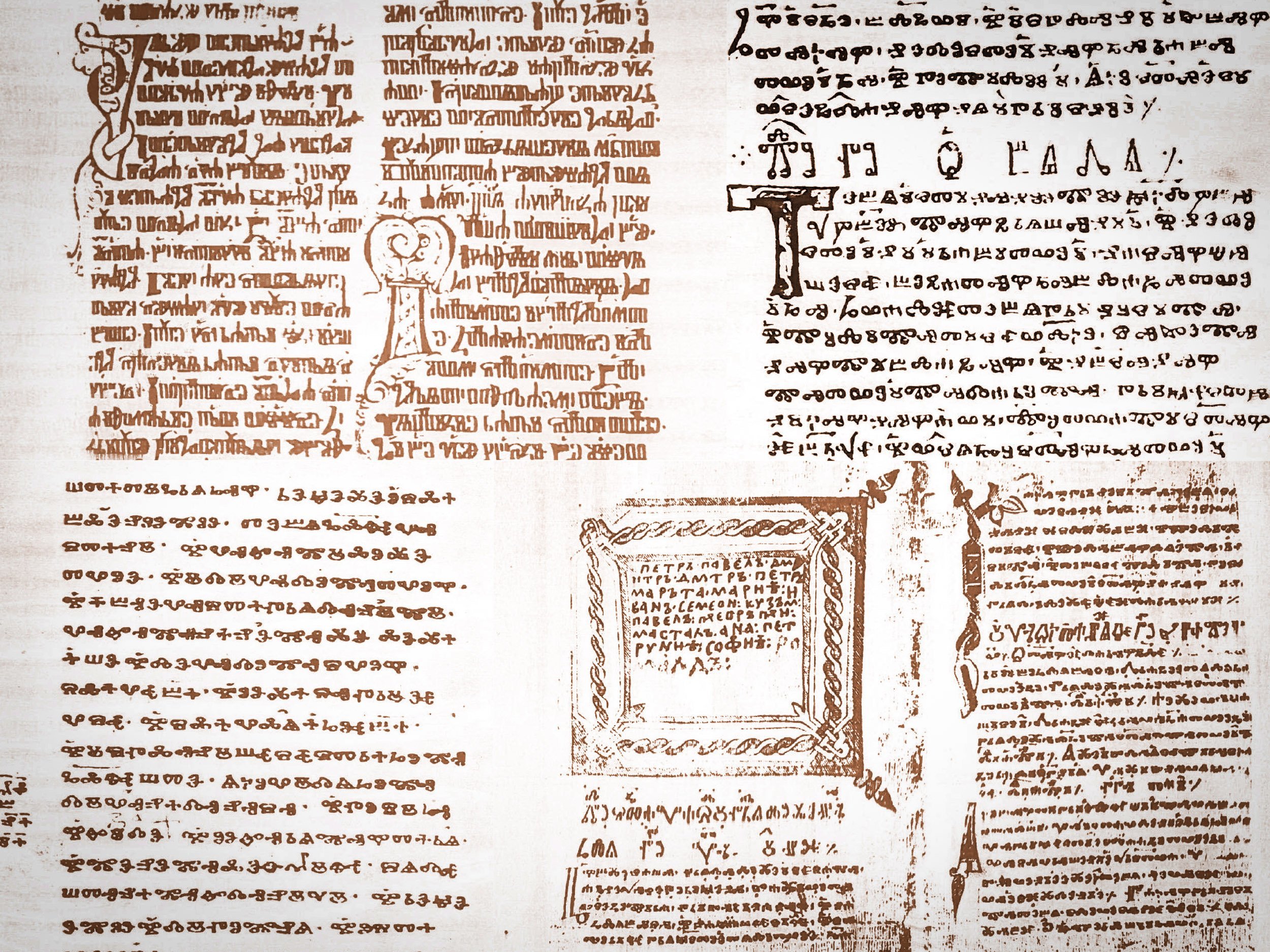

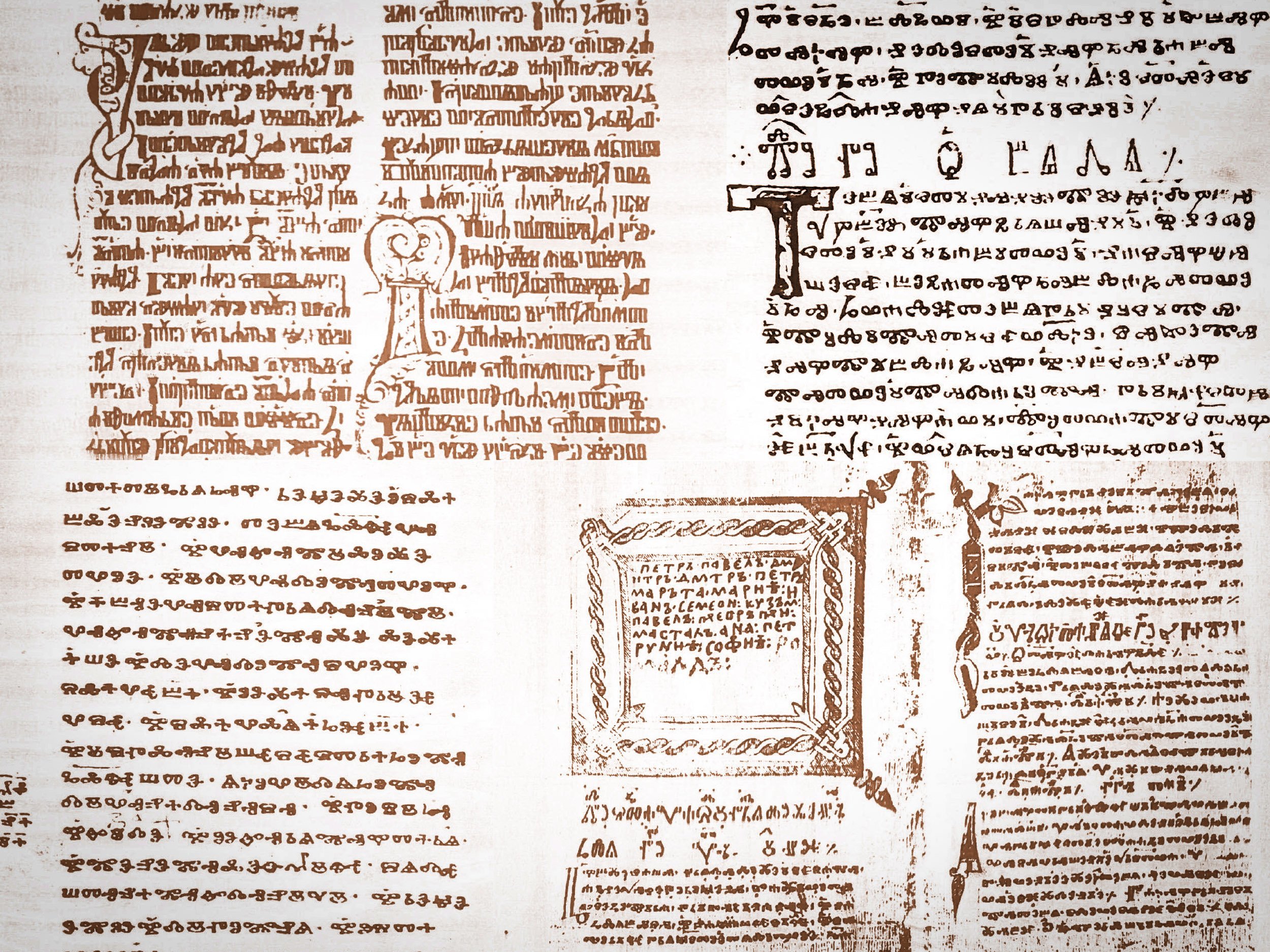

Author: Lebiba Džeko, MA, National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina • Illustration: Different writing styles used in Bosnia for centuries • Source: Gazi Husrev-beg Library

Differences in overall circumstances in which Islam in Bosnia and Herzegovina developed led to significant diversity, primarily in the tangible culture characteristic for Bosnian and Herzegovinian Muslims. Muslims in whole Bosnia and Herzegovina are a single cultural and religious community which has been developing in different geographic, climatic, political and other conditions. In a way, Bosnia and Herzegovina is a geographic “miracle”, since in a relatively small area one encounters three climate zones which were preconditions for people's daily life adjusted to the diverse terrain (mountain and rocky regions, lowlands, coastal belt). The way of building private houses and facilities of public significance for the entire community – mosques, masjids and tekkes – was conditioned by natural factors. It was due to the availability of building material that a mosque was built of stone and had the stone minaret, or that it was built of adobe, with many wooden elements and a wooden minaret. Rural and urban ways of building also differed, since religious and public facilities in cities were larger and more monumental. Regardless of the differences in the way of building, the kind of building materials and whether a mosque was situated in a village or in a town, the interior decoration of mosques found its source in the Revelation and sunnah, and was an inseparable part of the overall traditional cultural-artistic expression of Islam.

Upon its arrival in the Balkans, the Ottoman State created new socio-economic relations which resulted in great and significant changes. The emergence and development of a large number of cities brought about the development of crafts and trade. In accordance with this fact, as well as in a permanent creative process of people who lived in this area, the daily life was enriched with new contents which were reflected in the manner of dress, household items, diet and some customs.

Still, the traditional manner of dress is a fruit of multiple cultural contacts and has been subject to constant change. In some cases, it is hard to determine the origin of some parts of folk costumes, since influences came both from the East and from the West. However, items which survived here and became usual among Muslim urban population were typically consistent in all urban environments. Differences were minimal, such as the height of fez in Sarajevo and Banja Luka costumes, slight differences in the cut of pants and others. The outward parts of men’s urban costumes, which could be seen, consisted of the sirwal or loose trousers which were ornated with tersian embroidery or with braids. The upper part of men’s urban costume differed: over the shirt, men could wear a fermen (vest made of wool or velvet ornated with braids which is not buttoned up), ječerma (vest made of wool, velvet or cotton ornated with silver or gilded strings of plates or buckles and with metal buttons), čevken (short jacket with long loose sleeves, ornated with gold or silver embroidery) or dolama (long robe open in front) and gunj (coat) or ćurak (furcoat) in winter. Ulama wore džube (cloak) of black cloth which had the same cut as ćurak but without fur. Footwear included mestve (boots made of soft leather, with very thin sole, without heels) and firale (shallow shoes worn over mestve). Heads were covered with the ćulah (caps of rolled wool, usually white) and, from the end of the 19th century, the fez.

Muslim traditional women’s costumes were typically influenced by Constantinople fashion. Over shirts, women in cities wore fermens, ječermas, digišlijas (furcoats ornated with silk braids), čevkens, čurdijicas (coats with fur lining) džubes and anterijas (silk overcoats). All the garments were worn with dimije (a kind of sirwal pants), except for anterija, which was originally worn only over the shirt and later, from the mid-19th century, over thedimije as well. In the intimacy of home, the head was covered with the fez, tepeluk (caps ornated with strings of gold coins or pearls and embroidered with silver or gold) and other kinds of caps, an interesting kind being the so-called kalkan cap with a tepeluk (silver or golden plate) and dense, silver, black fringes that covered the hair and created the appearance of hair. In the street, women wore the feredža (overcoat of black or dark blue cloth) and the zar (cotton or silk wrap). The feredža gradually fell into disuse by the end of the 19th century and gave way to the zar, since it was easier to make. This manner of dress became less frequent as early as in the early 20th century, and completely disappeared in the second half of the 20th century.

Muslim costumes in villages were primarily conditioned by climate and terrain characteristics of the area where they were worn. The traditional rural costumes of Muslims differ by regions, and thus we distinguish costumes of Posavina, East Bosnia, Central Bosnia, West Bosnia and Herzegovina. Another significant factor which affected the traditional costumes in villages was the kind of work people were involved in. The clothes had primarily to be adjusted to the work on the land, minding the cattle, scything, and some of this work was done by women together with men. This was the reason why the hair was covered in a different way, clothes were more comfortable and almost all garments were homemade. By the end of the 19thcentury, purchased items began to be introduced in the traditional rural costumes, the first ones being thin scarfs for covering girls’ and women’s heads.

References:

Balić Smail, Kultura Bošnjaka muslimanska komponenta, Wien, 1973.

Bećirbegović Madžida, Džamije sa drvenom munarom u Bosni i Hercegovini, “Veselin Masleša”, Sarajevo, 1990.

Beljkašić Hadžidedić Ljiljana, Gradske nošnje u Bosni i Hercegovini u 19. vijeku, Katalog izložbe, Sarajevo, 1996.

Beljkašić Hadžidedić Ljiljana, “Prilog poznavanju seoske muslimanske nošnje u Bosni i Hercegovini”, GZM BiH, Etnologija, Nova serija, sv. 43/44, Sarajevo, 1989.

Beljkašić Hadžidedić Ljiljana, Gradske muslimanska tradicijska nošnja u Sarajevu, priručnik za rekonstrukciju narodne nošnje, Zagreb, 1987. (Biblioteka “Narodne nošnje Jugoslavije”)

Faroqhi Suraiya, Sultanovi podanici, Kultura i svakodnevnica u Osmanskom Carstvu, Zagreb, 2009.

Hadžihasanović Amra, “Metafizičke pretpostavke islamske umjetnosti dekoracije”, Znakovi vremena, Sarajevo, 2017, God. XX, broj 76/77.