FRAGMENTS FROM CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN RAIS ČAUŠEVIĆ WITH STATE AUTHORITIES

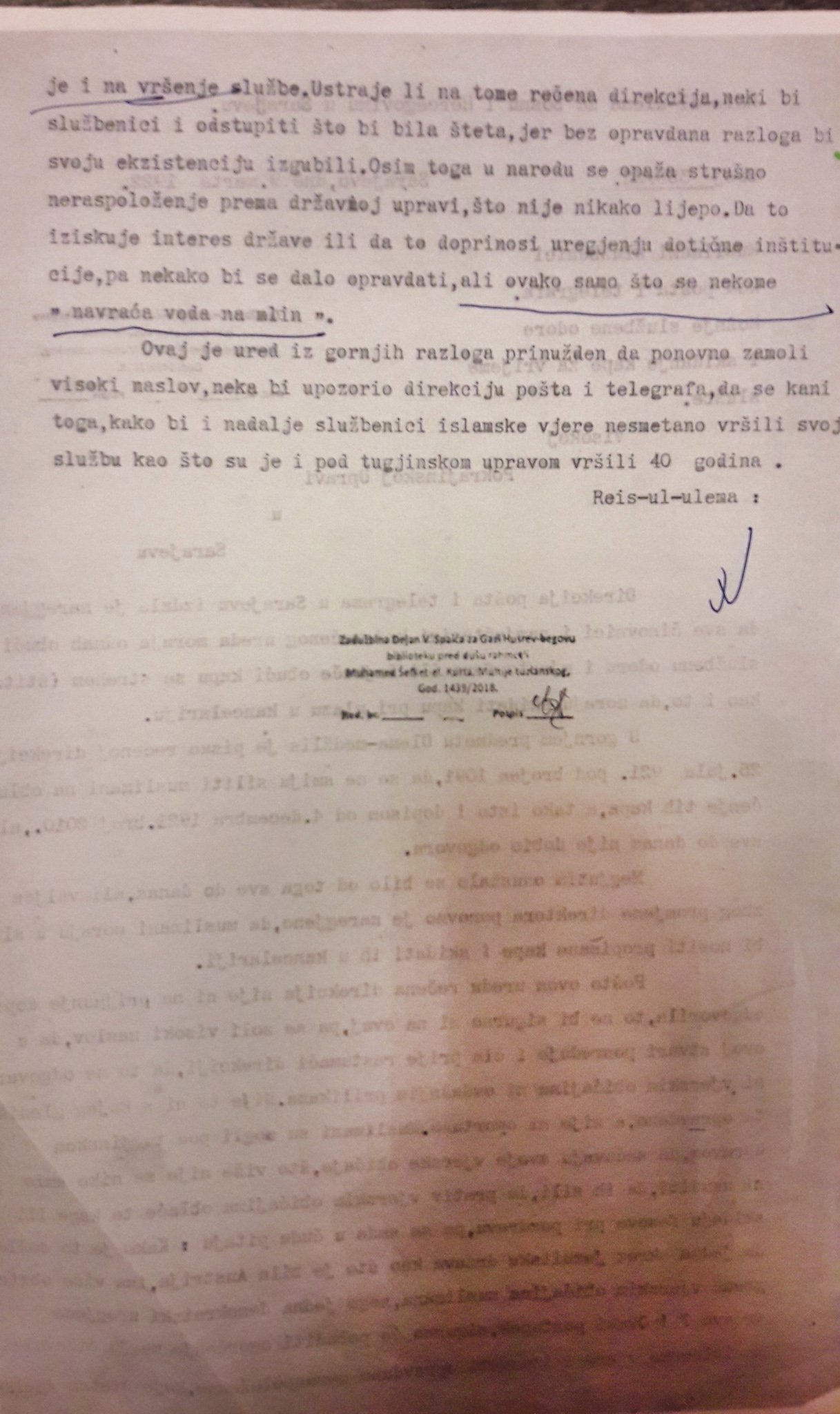

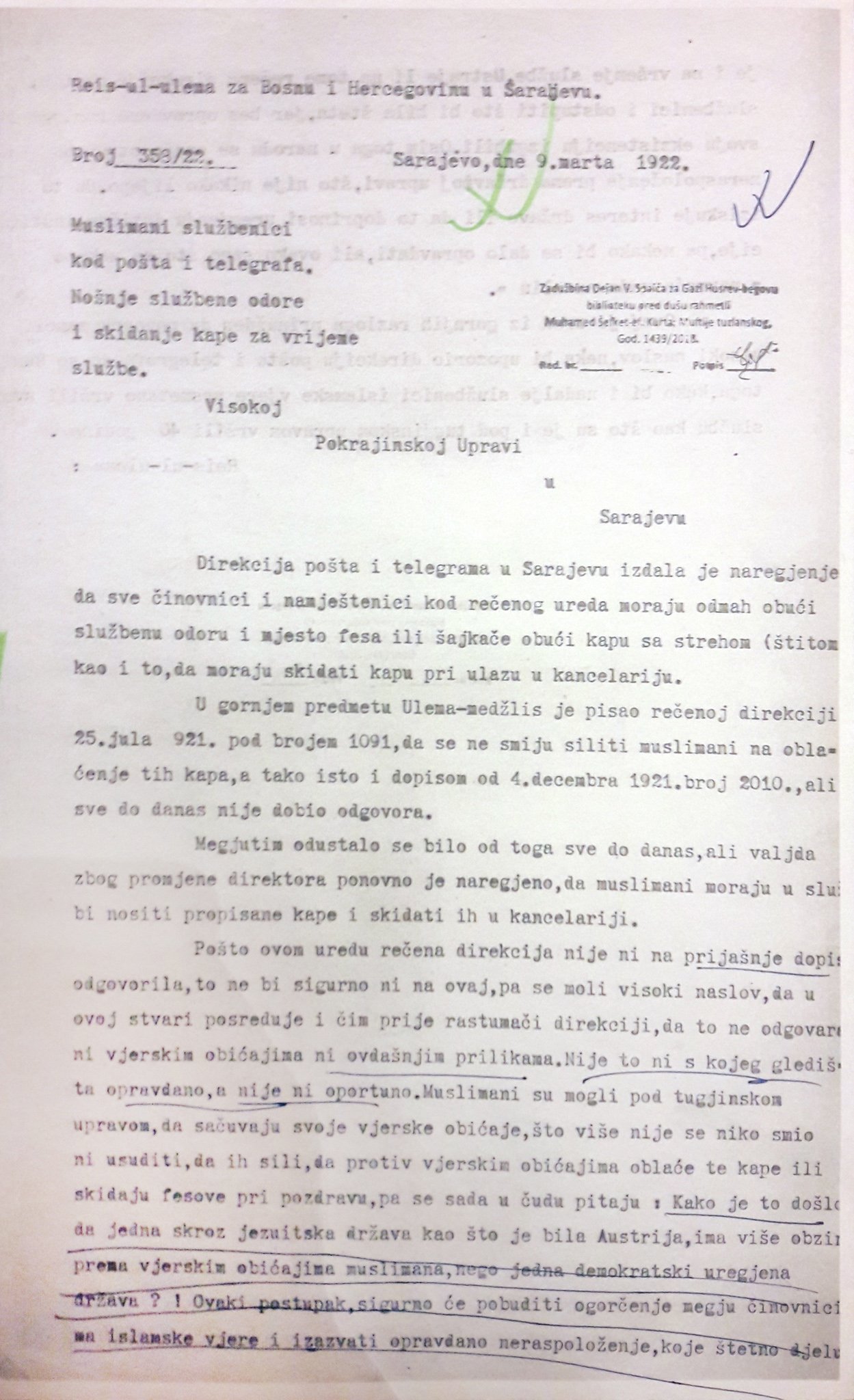

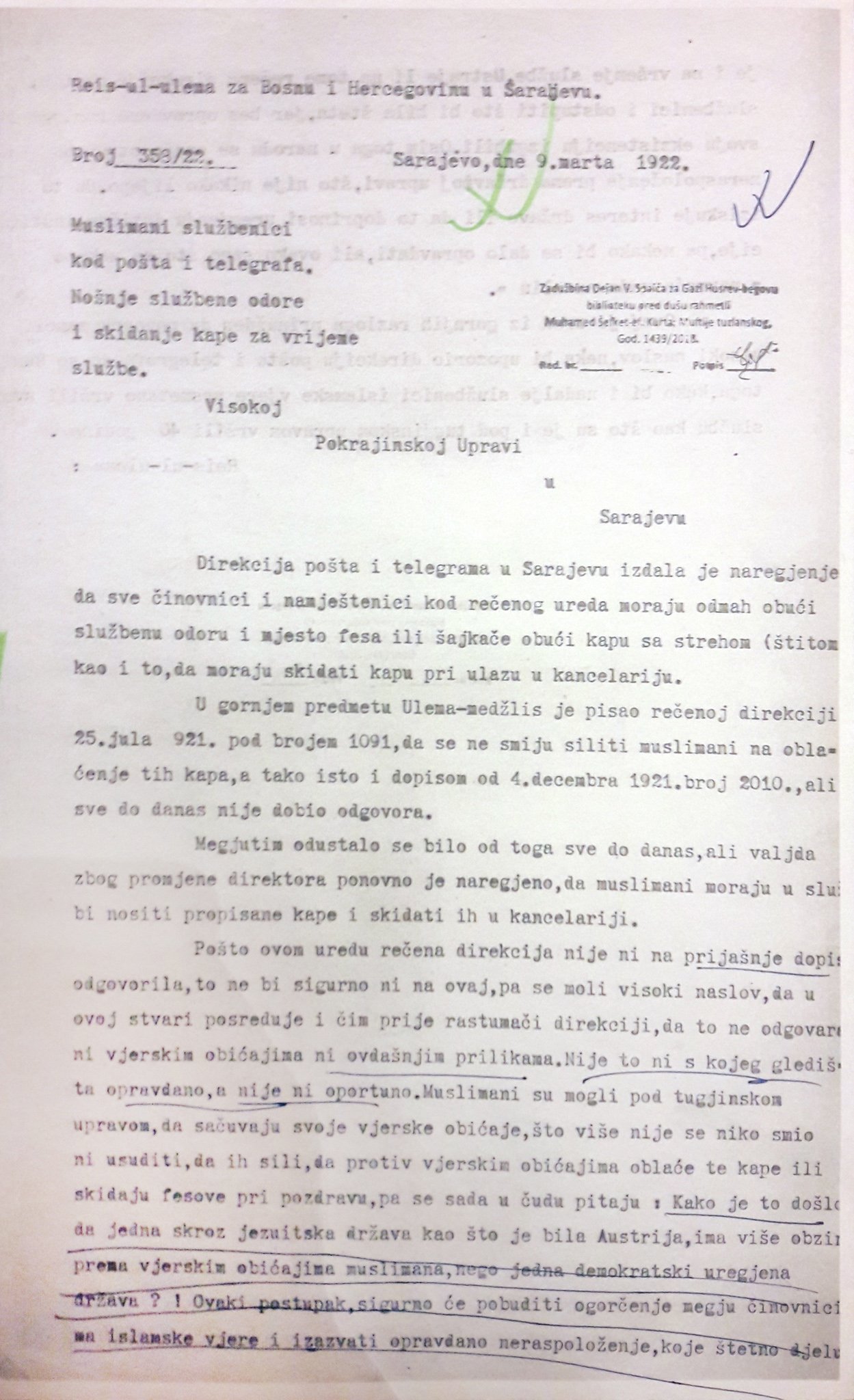

Author: Ilma Delić, MA • Illustration: Facsimile of the letters of rais Čaušević with state authorities • Source: Gazi Husrev-beg's Library

Almost a whole century has passed since the publishing of the book Islam and the Foundations of Political Power (1925) by the distinguished Egyptian scholar Ali Abdurrazik. At a time, this worked signaled a historical turning point and even today it causes violent reactions and is the topic of many debates. In brief, Ali Abdurrazik claimed that Islam does not advocate a particular form of rule. This famous author directs his criticism to those who use religious law for political proscriptions, as well as to rulers through history whose legitimacy was confirmed by caliphate:

There is not a single principle of the faith that forbids Muslims to co-operate with other nations in the total enterprise of the social and political sciences. There is no principle that prevents them from dismantling this obsolete system, a system which has demeaned and subjugated them, crushing them in its iron grip. Nothing stops them from building their state and their system of government on the basis of past construction of human reason, of systems whose sturdiness has stood the test of time, which the experience of nations has shown to be effective (Abdel Razek, 2013).

And while Ali Abdurrazik defended the ideas presented in this revolutionary essay in his own way, on the other end of the Mediterranean, about two thousand kilometers away, raisu-l-ulama of Bosnia and Herzegovina Džemaludin Čaušević practically fought (through) this issue. Everything that was included in the area of Islamic religious practice and was disputed or imposed by local authorities of the time had been previously gladly legitimized by the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In a letter which Čaušević addressed to the High Provincial Administration on 09 March 1922, “Wearing uniforms and taking off caps during service”, he appealed for abolishing measures which the minister of transportation Velizar Janković planned to introduce, saying that “whoever is not willing to comply should be dismissed from service”. The measures pertained to the dressing code for staff of the Directorate of post offices and telegraphs of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Pursuant to the measures, the staff were required “to wear uniforms and they have to put on the cap with the bill instead of the fez or the šajkača (Serbian traditional cap)”, and they “have to take the cap off when entering the office”. Naturally, Čaušević first addressed his letter to the Directorate which adopted this rulebook; however, since he did not receive a reply for some time, he contacted the higher relevant body. He asserted that this imposition of such a form of “uniform dressing” was pointless and tendentious because for Muslims, “although it is not forbidden to wear a billed cap, it is not in line with religious customs or local situation”. Čaušević then referred to ruling which had been issued by the War Department in Vienna nine years before. This Austrian department accepted raisu-l-ulama Čaušević's proposal and introduced “the grey cap instead the red one”, having abandoned the introduction of the “plain military cap with the bill”. Čaušević pointed out that this Austrian department had never maliciously referred to his interpretation of original Islamic regulations to revoke “exactly what he as a religious leader recommended to the government”.

Čaušević here referred to his correspondence with the Austro-Hungarian commanding general and provincial head in Bosnia and Herzegovina (kommandierender general und landschef) Sarkotić, which was characterized by the timely response to his letter, regular notices about the process of consideration and, finally, acceptance of all the requests which Čaušević had submitted as the “religious leader of Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina” pertaining to the interpretation of religion and religious regulations. To be precise, it was a letter of September 1815, where Čaušević complained of inappropriate treatment and unbecoming actions of military servants and hospital administrations toward Muslim soldiers. He described the issues of religious bathing, burial according to “rituals of another faith”, even the fact that Muslim soldiers were forced to “convert to another religion” when dying by Christian priests. He also wrote that they were sworn at “using what was the most sacred for Muslims”, and that the food contained pork meat. It went so far that Muslim soldiers, when they refused to eat food that is forbidden to Muslims, were told that such a diet was approved by the raisu-l-ulama himself. Čaušević received the response to this letter after nine days, and it included the following decisions about Muslim soldiers: permission to “attend the mosque”, permission to perform religious baths, prohibition for “priests of another religion to get in touch with Muslim soldiers in hospitals”, as well as the prohibition for them to bury such soldiers and – most importantly – the explanation that raisu-l-ulama Čaušević had by no means approved that Muslim soldiers “could eat pork, nor was it allowed”. Thus, not only all raisu-l-ulama Čaušević's requests were complied with, but he himself regularly received feedback during almost three months of the consideration process. Besides, general Sarkotić informed him that the “supreme military command had adopted regulations pertaining to performing Muslim religious rituals and they should be strictly complied with”. He also disavowed possible omissions and said that, if there were any, they had to be “attributed to distinctiveness of war relations, and by no means to evil intents or intentional circumvention of these regulations”.

According to what we have described, one should not be surprised by Čaušević's assessment of local authorities as those who “demean Islam with their attempts to unnecessarily confuse the already confused Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina”. Expectedly, Čaušević in this case preferred the Austro-Hungarian way of ruling, since “under their auspices Muslims could so nicely preserve their sacred faith, so that now they are not weaker in this respect than their brothers who live under caliphate rule”. Moreover, Čaušević wrote that “Muslims suffered more attacks on their sanctities over the previous four years than over 45 years of foreigners' administration” or that “under foreign administration Muslims could preserve their religious customs, moreover nobody could dare to force them to put on those caps or take off fezes when greeting somebody, which is contrary to religious customs, and are now wondering in surprise: how is it possible that a completely Jesuit country such as Austria respected Muslims' religious customs more than a democratically organized state?”

A reminder to this correspondence of Čaušević contributes to the search for the answer to an important question, which was raised in Abdurrazik's essay from 1925 and the discussion of which is still going on: how should Muslims be organized as a community?