RECEPTION OF THE BALLAD HASANAGINICA IN EUROPEAN CULTURE

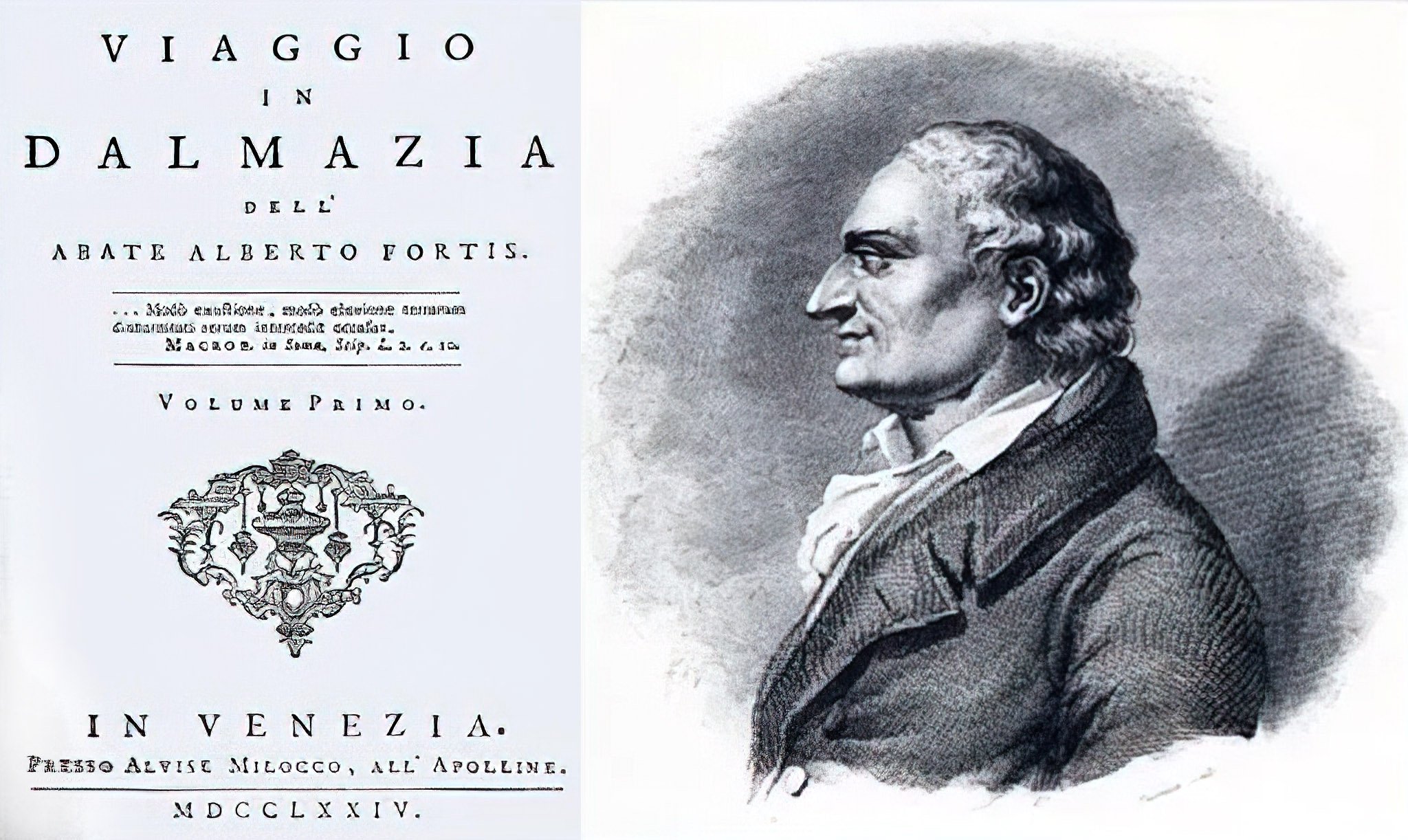

Author: Merjem Hodžić Jusić, MA • Illustration: Alberto Fortis: “A Journey to Dalmatia”, 1774

In terms of the European reception of works from the Islamic cultural circle in the Balkans, ballad Hasanaginica is certainly one of the most interesting works for analysis.

It is believed that the ballad about the tragic destiny of Hasanaga's wife, which was the inspiration for many studies and analyses, was created in Imotska Krajina in the period between 1646 and 1649, during the rule of the Ottoman Empire in these regions, and that it was transmitted orally for years.

The story of its reception begins in the 18th century, when Italian travel writer and scholar Alberto Fortis found the text of the ballad and had it published in his work Put u Dalmaciju (A Journey to Dalmatia) (1774). Fortis went to Dalmatia to describe geological phenomena and archeological artefacts, aiming to explain how these regions could be made the best use of economically. However, what aroused his greatest interest, and later on the interest among Western European readers, were folk creations by local population, and the chapter where Fortis described the life of Morlaks, people who lived in today's Dalmatia hinterland, and which also included the text of the ballad.

Without resorting to stereotypes, Fortis described the origin, customs, beliefs, eating habits, abilities, weddings, music, dance, songs and poems of this South Slavic nation, who was completely unknown to the Western European culture (Bratulić, 1984).

However, what has partly remained unclear and in what critics disagree is the answer to the question as to how Fortis obtained the text of the ballad. Some claim that he could obtain the already written text from linguists - friends of his who were from this region, while others say that he could also hear the ballad from his housekeeper Stana, who drew her origin from Dalmatia hinterland, and that in this case he wrote it himself (Muljačić, 1973: 277-288).

After Fortis had introduced the ballad Hasanaginica to the Western European culture, i.e. after he had opened the door to its reception in the European culture, many great names of the European literature began to deal with the ballad and translate it. Some of them are: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Walter Scott, Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, Adam Bernard Mickiewicz and others.

German professor of Slavic studies and literary critic Gerhard Gesemann said that no other folk poem had been the object of so much love and hard work as the ballad Hasanaginica (Isaković, 1975: 65).

Still, the author who was particularly enchanted with the character of Hasanaginica and the love story between her and Hasanaga, where he could find elements of his own love stories with beloved women whom he left and hurt is the greatest German writer of all times, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The first German author who translated Hasanaginica in 1775 was August Clemens Werthes, and Goethe translated the ballad after him, using both Werthes's translation and the original version of the ballad. Thanks to the original version of the ballad, Goethe managed to preserve the same word order and rhythm (Schubert/Krause, 2001: 16). To do so, he used groups of words which are repeated, the so-called epic repetition, which is one of the characteristics of South Slavic poetry to which neither Werthes nor Fortis before him paid attention. Goethe’s translation was first published anonymously in Herder's collection of Folk poems from 1778, and under his name it was first published in 1789 in collected writings. It is interesting to study and write about everything that made Goethe develop an interest in this ballad. Certainly, it includes his general interest in the Oriental world, though some other factors as well – his interest in the role of the woman and her relationship with her husband. Goethe was always interested in the woman's psychology, and he was particularly moved by the character of Hasanaginica, whom the ballad depicts as a woman who does not complain but rather accepts her destiny as it is and bravely faces it. In her character Goethe saw a kind of contrast to Hasanaga's modern and romanticist actions. Many literary critics reached the conclusion that Goethe's involvement in Hasanaginica was marked with his own love experiences from the real life, i.e. that he used Hasanaginica to overcome the destructive, negative energy in himself in his relationship with his beloved Anna Elisabeth Schönemann, called Lili.

Thus, unlike many other European intellectuals who dealt with Hasanaginica and translated it, Goethe did not have a problem with understanding the character of Hasanaga, since it was easier for him to connect to Hasanaga's Eastern soul and his unusual love for a woman (see Ćurčin 1974; quoted according to Buturović 2010: 65). It is a love which gives strength and destroys at the same time; the love is fatal both for Hasanagica, a woman who dies after she has been forced to part with her children, and for Hasanaga himself, in whose words and addressing children Camilla Lucerna, a Croatian writer and translator of the first half of the 20th century, also sees elements of love and multilayered character and cannot unambiguously label him as a “villain” (Lucerna, 1943: 51).

It should also be noted that Goethe's dealing with Muslim ballad Hasanaginica was of great significance for his later involvement with the Oriental, Islamic world and for writing his famous collection of lyric poems West-Eastern Divan.

The complex and multilayered character of Hasanaga and the brave and noble Hasanaginica aroused interest of many European intellectuals, literary critics, translators and writers; still, two cultures stand out most in this respect – Italian, where the ballad first appeared, since Italian scholar and travel writer Alberto Fortis was the first to discover and write the text of the ballad; and German culture, which engendered several translations of the ballad, the translation by the greatest and the most versatile German writer of all times, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, certainly being the most significant. Goethe was enchanted by the character of Hasanaginica, her role in the marriage, family, society and the love between her and her husband Hasanaga in whose actions he saw some modern, romanticist desires and views.

References:

Buturović, Lada (2010), Treptaj žanra u poetici usmene književnosti, Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

Fortis, Alberto (1984), Put po Dalmaciji (hrvatsko izdanje priredio: Bratulić, Josip), Globus, Zagreb.

Isaković, Alija (1975), Hasanaginica, Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

Konstantinović, Zoran (1970), “Komentarˮ, u: Eckermann, J.P.: Razgovori sa Goetheom, Kultura, Beograd, u: Alija Isaković (1975), Hasanaginica, Svjetlost, Sarajevo, str. 91-92.

Lucerna, Camilla (1943), Balade “nepoznatihˮ, Studija o hrvatskoj narodnoj poeziji, (Balladen der “Unbekanntenˮ, Studienblättchen zur kroatischen Volkspoesie), Matica Hrvatska, Zagreb.

Muljačić, Žarko (1973), “Od koga je Fortis mogao dobiti tekst Hasanaginice?ˮ, u: Alija Isaković (1975), Hasanaginica, Svjetlost, Sarajevo, str. 39-49. (Prvi put objavljeno u: Radovi Filozofskog fakulteta Zadar, 11, Odjel za Lingvistiku i Filologiju, 1972/1973, Filozofski fakultet Zadar, str. 277-288.)

Schubert Gabriella, Friedhilde Krause (2001), Talvj, Therese Albertine Luise von Jakob-Robinson (1797-1870), Iz ljubavi prema Goetheu: Posrednica balkanskih Slavena, (Talvj, Therese Albertine Luise von Jakob-Robinson (1797-1870), Aus Liebe zu Goethe: Mittlerin der Balkanslawen), Verlag für Datenbank und Geisteswissenschaften, Weimar.